Jean Rhys - From Dominica to Cheriton Fitzpaine

Back in the early days of spring, I received notice that the university were to put on an evening celebrating the life and work of Jean Rhys in the village which was her home in her latter years, Cheriton Fitzpaine. I knew something of her peripatetic life, but nothing beyond a few generalities. Clearly it was time to go sleuthing in the stacks once more.

The writer later to be known as Jean Rhys was born Ella Gwendolin Rees Williams in 1890 on the island of Dominica. Dominica was one of the Windward Isles, which bracketed the Caribbean on its Eastern edge. Rhys was a member of a decaying aristocratic class, her ancestors plantation owners and therefore also slave owners. She lived in Dominca for the first 16 years of her life before moving to England in 1907. Her pronounced accent and financial insecurity, along with a strong independent spirit, made it difficult for her to fit in. This sense of marginality would be with her throughout her life.

Attempts at becoming an actor at an early incarnation of RADA foundered, and she fell into the gruelling routines of a chorus girl in a touring summer repertory company. She worked in an army canteen in Euston Station during the war. A month’s holiday in Crickley Cottage in the Vale of Evesham, Glos., in which one of her companions was the wild-living Philip Heseltine, later to rechristen himself as a composer named Peter Warlock, provided material for a later short story entitled Till September Petronella. Heseltine becomes the character Julian Oakes

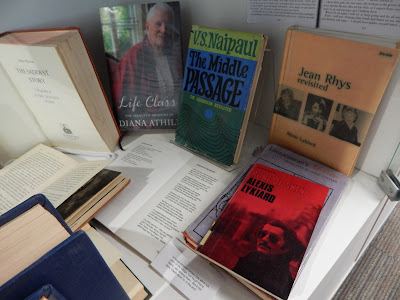

The 1920s found her in bohemian Paris, where she started writing in earnest. She enjoyed the patronage of the author Ford Madox Ford, moved in with him and his artist wife Stella Bowen in 1924 and had a brief affair with Ford. He wrote a rambling preface to her first book, a short story collection entitled The Left Bank, in which he briefly voices his admiration for her in between his own guide to the Parisian Left Bank scene. It appears we have a first edition of this collection down in the stack. It was at this point that ‘Jean Rhys’ was born as a writer’s name.

Ford would later be portrayed in a less than flattering light as the character Hugh Heidler in Rhys’ 1928 novel Quartet, with Stella Bowen recast as Lois Heidler. Bowen’s own reminiscences of this period can be found in her 1940 memoir Drawn From Life, in which an unnamed Rhys is torn apart. Her ‘world’ is likened to that of Louis-Ferdinand Céline and Henry Miller, and it’s not supposed to be a compliment (although Rhys loved Céline’s Voyage to the End of Night). Ford Madox Ford provided his own fictional portrait of Rhys in his 1931 novel When the Wicked Man. Again, it’s not exactly a loving representation. Rhys read Arthur Mizener’s 1971 biography of Ford, The Saddest Story, and was deeply upset by her portrayal, which once more cast her as the disruptive temptress.

Rhys’ 1939 novel Good Morning Midnight is now widely regarded as a masterpiece. However, its downbeat tone led to negative reviews at the time. It is a portrayal of a woman in her late middle age living a marginal life in Paris, on the edge of poverty and trying to stave off despair. The first person stream of consciousness narrative gets into the mind of the troubled protagonist to an intensely empathetic degree. The novel's failure was a huge setback for Rhys. It was to be her last published novel for 27 years.

The 40s and 50s were, in some ways, Rhys’ ‘lost years’. The violent tempers which accompanied her heavy drinking got her into trouble, including a few days remanded to the hospital wing of Holloway Prison. She continued writing, however, and some of the short stories produced at the time would later be gathered into collections after the success of Wide Sargasso Sea.

7 years later, BBC producer Sasha Moorsoom was advised by Vas Dias to use a similar approach to contact Rhys regarding the radio play of Good Morning Midnight. After a number of altercations with neighbours during a particularly chaotic period of her life, Rhys and her husband Leslie Tilden-Smith had retreated to Bude. Once more this contact raised her spirits and encouraged her to write again. Had it not been for these two ads, themselves acts of sleuthing, it is highly unlikely that the world would ever have seen Wide Sargasso Sea, the novel Rhys had been contemplating for some years. Knowing that we had bound back issues of the New Statesman down in the stack, I set about tracking these ads down. There was a particular thrill in finding them. Humble and throwaway as they might appear, these represent those tiny, incidental turning points which redirect the flow of history (personal or otherwise) and lead to momentous events.

The success of the radio dramatisation of Good Morning Midnight, finally broadcast in May 1957, led to two people who would be very important to Rhys getting in touch – editor Diana Athill and writer Francis Wyndham, both of whom worked for the publisher Andre Deutsch. They signed her up for an option on the novel she was working on, which Rhys promised would be ready by the next year. Thus began the long and torturous path towards the publication in 1966 of the book for which she is still best known, Wide Sargasso Sea. Much of this would be written in her cottage in Cheriton Fitzpaine. In a strange way, then, it could be said to be one of the most famous novels ever to have come out of this county.

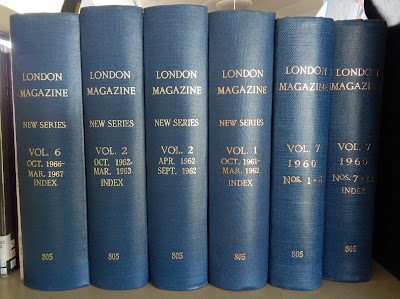

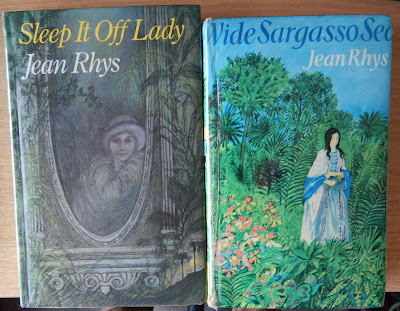

Wyndham’s literary connections led to the publication of several of Rhys’ short stories being published in the London Magazine, as well as a story in the 1960 collection Winter’s Tales 6. We have a run of bound copies of London Magazine in the stacks, including their colourful covers, so I was able to find the original publications of these stories. We also have a run of the Winter’s Tales short story anthologies, so I plucked volume 6 off the shelves too. Given the lengthy gestation period of Wide Sargasso Sea, these short stories were important in maintaining Rhys’ revived literary reputation. A later collection of short stories, Sleep It Off Lady, would be published in 1976, including her haunting short (very short) ghost story I Used To Live Here Once - an appropriate way to finish off her final book of fiction.

Our stack copy of Wide Sargasso Sea is a 1974 reprint, but the cover is the same one used for the 1966 first edition. It was not Rhys’ choice. She wanted to use one of the paintings of Dominica by her aunt Brenda Lockhart. This would have emphasised the personal connection she felt with the West Indian (specifically Dominican and Jamaican) setting of the first part of the novel.

Wide Sargasso Sea is now regarded as a classic of 20th century literature, and is a standard book on school and university syllabuses. Reviews at the time were ambivalent, however, writers once more decrying its downbeat tone. The assessment by Alan Ross in London Magazine (of which he was the editor) was more in line with future opinion, however. He wrote that whilst ‘it was no less despairing and disastrous in outcome than the early books, it has a sensual lushness and bloom about it that, to anyone who knows the West Indies, is quite overpowering. As an act of literary re-creation it is astonishingly convincing; as a novel of nineteenth century West Indian life it achieves a haunting beauty that has, in its genre, few equals; and finally, in its weird and affecting pre-dating of Jean Rhys’ other heroines, Anna Morgan and Sasah Jensen, alike victims of their own attractivenes, predatory temperaments and unyielding honesty, it completes a satisfying circle’.

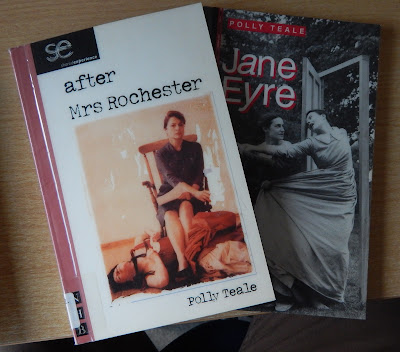

Having adapted Jane Eyre for her company Shared Experience Theatre in 1997, Polly Teale wrote a play about Jean Rhys’ life called After Mrs Rochester, which was first performed in 2003. Rhys was played by Diana Quick. We have copies of both her Jane Eyre play and After Mrs Rochester in our collection of playscripts down in the stack

V.S.Naipaul was a fellow ‘exile’ from a West Indian upbringing, and was also under the editorial guidance of Diana Athill. His 1962 travel book The Middle Passage was controversial in its negative portrayal of the Caribbean. In 1972 he wrote an appreciation, one of the first and most insightful, of Rhys’ work in the New York Review of Books. Rhys was hugely appreciative of this acknowledgement.

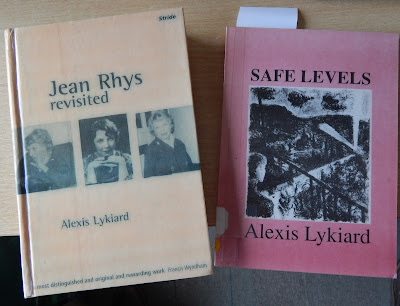

Rhys spent the last 19 years of her life in the village of Cheriton Fitzpaine near Crediton. Although she constantly complained about it in letters to friends, this was the most stable base she ever had in her life. She relied on the visits of the mobile library for her reading matter. Despite complaints that the villagers hated her, she built up some good friendships and had a number of supporters who helped her as she worked on Wide Sargasso Sea. One of her regular visitors was the poet Alexis Lydiard, who shared her love of French literature. He introduced her to Lautreamont’s Chants du Maldoror, which he had translated. He wrote two anecdotal books about Rhys, one of which, Jean Rhys Revisited, we have a stack copy of. We have a number of his poetry collections too, including the 1990 collection Safe Levels which includes a tribute to his late friend, also entitled Jean Rhys Revisited.

Comments

Post a Comment