Poetic Signatures

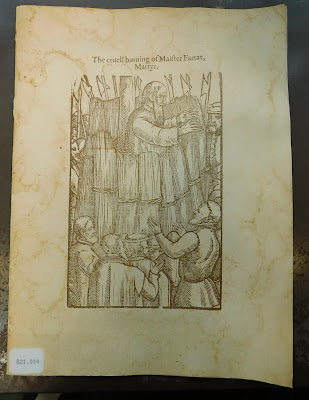

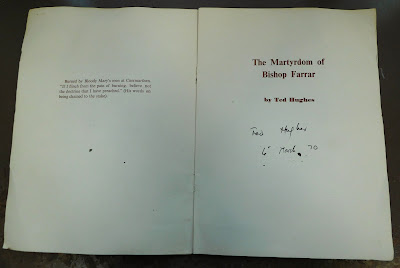

Amongst the Ted Hughes books with their Faber and Faber covers and illustrations by Leonard Baskin is interleaved a thin booklet, rather ageworn and bearing the stains of careless use or incautious storage. It's a reprint of an early poem published in 1957, from an age before Hughes was lionised as a literary giant and demonised by some who chose to cast him as villain in their mythologised script of a real life tragedy. The historical subject of The Martyrdom of Bishop Farrar might have seemed an appropriate one to revisit. It certainly had a personal resonance for Hughes in that Bishop Farrar, a martyr from the period of Queen Mary's Reformation reversing persecutions (he was executed in 1555), was a distant ancestor on his mother's side. This is the second printing of this pamphlet. Hughes and the publisher rejected the first, which had errors in its printing. It hadn't been set straight on the page and two lines had been swapped around. It differed from the version seen here in that it had a marbled magenta and light blue cover with the print of Bishop Farrar's martyrdom somewhat obscured as a result. The printing error evidently occasioned a rethink on this front as well, and the version seen here allows the print to come across with far greater clarity. It's a woodblock print taken from Foxes Book of Martyrs. Incidentally, we have several copies of that down in the special collections in the stack 'cage' area - a real repository of treasures.

Ted's clearly scrawled his signature with a scratchy old nib dipped into the inkwell, leaving a spattering of blots. Perhaps in a hurry to get through his alloted pile of signing, he evidently closed the pamphlet anyway, creating a mirror blot on the inner page. Amateur psychologists can read into this what they will. It leaves a pleasing impression of the activity of the moment which a neater inscription would lack, anyway.

The booklet was part of The Manuscript Series published by Richard Gilbertson from his base in the village of Bow to the west of Crediton. Gilbertson was a bookseller who published a slim volume of verse himself entitled A Cornish Aerie. This was published in a run of 175 copies with an illustration by the artist Rigby Graham. We have a couple of small press booklets of single poems by John Clare which are illustrated by Graham in a style which resembles neo-romantic British artists like John Piper and Graham Sutherland. Also around this time, in the late 60s and early 70s, Gilbertson published similar limited run printings of Hughes' Five Autumn Songs for Children's Voices and Animal Songs, Thom Gunn's The Explorers, Seamus Heaney's Night Drive and Kathleen Raine's A Question of Poetry. He seems to have moved down to Cornwall sometime in the 70s, and there is an article by him in the Antiquarian Book Monthly Review from 1980 titled DH Lawrence in Cornwall in which he explores the local literary landscape.

Gilbertson is likely to have had some contact with Ted Hughes. Just a few miles west of the village of Bow where he was living, a quick motor or cycle along the A3072, brings you to the small town of North Tawton. It was here that Hughes bought Court Green, an 18th century thatched manor house, moving in with his wife Sylvia Plath in 1961. In 1970, he was living there with Carol Orchard, whom he married in that same year. Hughes maintained the house, although often resident elsewhere, until his death and his funeral service was held in North Tawton church. Carol Hughes has continued living in their home until the present day. It was also in Court Green that Hughes wrote Crow, one of his major works, which was first published in 1970. So the year in which he scratched his signature was one of considerable importance for him. It can only be speculation, albeit informed rather than idle, but I can imagine him sitting in his Devon retreat working his way through the 100 copies of Bishop Farrar with furious intent.

Down in the special collections area known, with sinister overtones belying its true nature, as the cage can be found an unassuming collection of pocket-sized books with cloth spines and faded blue boards. These are all publications from a small Irish publisher called the Cuala Press, and amongst them is our next signature from a poetic giant - none other than the great William Butler Yeats. Let's investigate the collection a little further to provide some context for this startling discovery.

Bookplates in several of the books make it clear that this was the collection of one Dr W.A.Cadbury. We can easily deduce that this was William Adlington Cadbury. A handwritten dedication from Elizabeth Yeats in one of the later Cuala Press books, a bibliography from 1933, gives appreciation and gratitude to William A Cadbury and Emmeline Cadbury. William Cadbury had married Emmeline Hannah Wilson in 1902. Emmeline had compiled a miscellany, A Message for Everyday, in 1923 which was privately printed by the Cuala Press in a small run of 24, with Elizabeth Yeats providing illustrations. It's both clear that these are the Cadburys in question and that they were active in their support for the press to the extent of ordering their own personal volume.

William Cadbury was a scion of the Cadbury chocolate clan. He was the second son of Cadburys founder Richard Cadbury and the brother of George Cadbury. It was George who really established the firm as a household name and a byword for chocolate as the world progressed into the twentieth century. The Cadburys' Quaker convictions also gave them a great sense of moral and social responsibility. In 1879, George supervised the relocation of the Cadburys factory to the outlying village of Bournville, a few miles from the centre of Birmingham. He instigated the building of a model housing estate for the workers, buying up surrounding land to ensure that slum housing didn't accrete around the new industry. This arrangement was formalised with the setting up of the Bournville Village Trust in 1900. William did his bit for the family firm too, bringing similar Quaker convictions to bear upon his activities. These were also informed by his own love of art and culture. In 1905 he commissioned the first Cadbury logo. He happened to be living in Paris at the time, and chose a Parisian artist for the job, one Georges Auriol. Auriol was responsible for the design of the Metro signs which still lend such a distinctive Art Nouveau air to older areas of the city.

.JPG)

A cosmopolitan man, Cadbury made several visits to Ireland and to West Africa, areas which exerted a particular fascination over him. The Cadbury company sourced its cocoa from West Africa, and in particular, from 1886 onwards, from the Portugese colony of Sao Tome off the West coast north of Gabon. In the early twentieth century, it became increasingly clear that labour conditions had regressed into what was, to all intents and purposes, slavery. William led the company's investigations into these conditions, visiting the island himself in 1908. In 1909 Cadbury's ceased purchasing cocoa from Sao Tome, and his efforts helped to bring other chocolate producers (including Fry's and Rowntrees) to boycott the plantations there. His own book on the subject, Labour in Portugese West Africa, was published in 1910. When he set up the William A Cadbury charitable trust in 1923, West Africa and Ireland were both beneficiaries of its grants. It also made significant contributions to the social infrastructure of Birmingham (of which he was Lord Mayor from 1919-21), with help towards the building of the new Queen Elizabeth hospital and sustained support for the library and art gallery (two institutions close to William Cadbury's heart).

The dedication above indicates that the Cadburys, William and Emmeline, had some connection with Elizabeth Yeats, even if it was just through the support of her press. Elizabeth was the brother of WB Yeats. With her sister Lily and someone called Evelyn Gleeson she had established Dun Emer Industries in the town of Dundrum on the edge of Dublin (it's now a suburb of the city) in 1902. This was intended as a William Morris style arts and crafts enterprise, with Lily and Loly (as Elizabeth was known to her friends) being in charge of the printing side of things whilst Evelyn looked after the weaving and embroidery. It was named after Lady Emer, the wife of the legendary hero Cuchulainn who was renowned for her needlework skills. The illustration on the title page of early Cuala Press and Dun Emer books, drawn by Elinor Mary Monsell, depicts Lady Emer leaning with willowy art nouveau languor against a tree. Things didn't work out as planned, however, and the two halves of the enterprise soon went their separate ways. The Yeats sisters branched off as Dun Emer Industries in 1904 and pursued their literary endeavours with the Dun Emer press. Elizabeth had been a part of William Morris' circle in the latter part of the 19th century and had been encouraged to learn the art of printing and typography by Emery Walker, who had worked for Morris' Kelmscott Press. Incidentally, we have a number of very fine Kelmscott Press books down in the cage. It's a subject we shall return to in a future post. Elizabeth even used the same kind of printer that the Kelmscott Press had employed - an Albion press, a heavy piece of hand-operated machinery which she learned to operate herself.

The first book the sisters published was In The Seven Woods: Being Poems Chiefly of the Irish Heroic Age by brother Willy - William Butler Yeats to the wider world. William had assisted with the setting up of the press and was semi-officially its literary editor. There were considerable tensions between Elizabeth and William, both of whom were strong, forceful personalities. Elizabeth had to be firm in asserting her overall control over the press (she was already in charge of the practical and business side of things). This was particularly important since, from the beginning of the Dun Emer project, the decision had been made to employ a solely female workforce. This included giving opportunities to teenage girls from the surrounding countryside, helping them to become independent and self-supporting.

Elizabeth Yeats learned much from the Kelmscott Press, but she rejected its focus on the past, its concentration on medievalism and chivalric dreamworlds. She was intent upon publishing new work by contemporary Irish writers, as well as reinterpretations of tales from the traditional Irish mythos. The first publication was emblematic, in a sense, and she would return to Irish mythology in several further volumes. The Cuala Press and its Dun Emer predecessor played an important part in the encouragement and promulgation of the Celtic Twilight movement of the late 19th and early 20th century, of which WB Yeats was a central motivating force, and which sought to revive a national literature. In 1908, Elizabeth and Lily moved operations to Cuala Cottage in Churchtown, Dundrum, and it was from this time that Dun Emer transmuted into The Cuala Press. Elizabeth remained in charge until her death in 1940, after which the press continued for a further 6 years, finally closing down in 1946 (although such was its reputation that it was later revived in a different form). In that 38 year period, Cuala had published 77 books. Elizabeth was buried in the churchyard of St Nahi's in Dundrum, the town from which she had operated (in an abstract and literal sense) the press for so many years.

There are a few other significant signatures in amongst William Cadbury's old collection. One is from Lady Augusta Gregory, at the end of her collection of lyrical translations of the old Irish verse. Lady Gregory was another important figure in the Celtic Revival. Her house and its estate at Coole in Galway was an important meeting place for the literary figures of that movement, WB Yeats included. One of his best known poems, The Wild Swans at Coole, was inspired by the surroundings. It was also at Coole that he met Evelyn Gleeson, the Yeats sisters' initial collaborator in the Dun Emer enterprise. Lady Gregory had also joined WB Yeats and Edward Martyn and others in forming the influential Irish Literary Theatre and later the Abbey Theatre (or the National Theatre of Ireland), where plays by the likes of Yeats, JM Synge and Sean O'Casey, as well as Gregory herself, were first performed. Her message to William Cadbury, written on March (?) 23rd 1918, has a touch of aristocratic hauteur about it: 'I write my name here for W.Cadbury, and hope he will not be disappointed in the book'.

F.R.Higgins has also signed his poetry collection Arable Holdings. This was the fourth of his five collections, published 1933. He was also involved with the Abbey Theatre as manager, director and latterly board member. A student and friend of Yeats, he was a lesser know member of the Irish literary scene, but his poetry was held in high regard by those who knew it.

Elizabeth Yeats' written dedications to William and Emmeline Cadbury trace the path of their relationship from the immediately post-war period to her 1933 note thanking them both for their support (this one signed from Dublin, Dundrum having no doubt been incorporated within its bounds). One of the notes is particularly interesting from a historical point of view. Elizabeth writes in 1923 of 'the first Cuala book issued from Senator WB Yeats' house'. This is an acknowledgement of Yeats' appointment as a senator for the new Irish Free State in 1922.

These are lovely books, lovingly made using local Irish paper from Saggart Mill in Dublin. They document a key period in Irish literary history, but also the course of a personal relationship between Elizabeth Yeats and the Cadburys. A meeting of worlds, of the Quaker businessman with his family chocolate empire and the sister of the great Irish literary family, striving to make her own mark on the cultural world. How wonderful to have them in the Exeter Library collection. As to how they got here, why William Cadbury, with his strong Birmingham roots, should donate them to a library in Devon....well, that remains a mystery.

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

Comments

Post a Comment