The New Naturalists

These spines tell us that the publisher is Collins, the publishing company set up in Glasgow in 1819 by one William Collins, a Presbyterian schoolmaster. Above this are the conjoined letters NN, printed in varying colours and contained with an oval bubble, often incorporated into the broader design. This stands for New Naturalist, for this is the series in question. The number at the top, again encircled in a round bubble and printed in varying colours (and fonts) tells us how far we have come in the series. So what are the New Naturalists, and who designed those beautiful covers?

The New Naturalists were a series set up in the post-war period which aimed at providing authoritative works on different subjects whilst still being accessible to a general readership. The editorial ideal for the series was set forth thus: ‘To interest the general reader in the wild life of Britain by recapturing the inquiring spirit of the old naturalists’. It’s an interesting perspective, with an implied nostalgia for a golden age of amateur naturalism, of the Victorian enthusiasts who developed expert knowledge through extensive observation. One member of the founding editorial board was biologist (and sometime director of London Zoo) Julian Huxley, so perhaps he had in mind his grandfather, Thomas Henry Huxley, popularly known as ‘Darwin’s Bulldog’ for his strident advocacy of evolutionary theory.

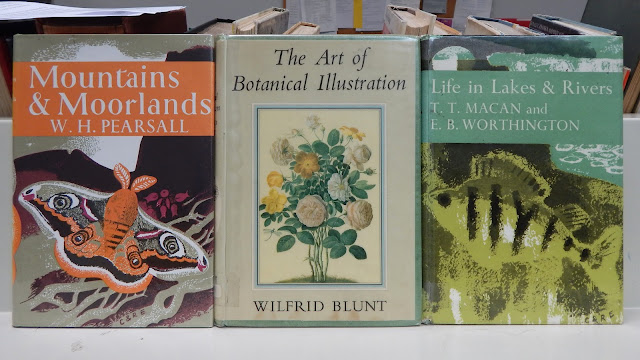

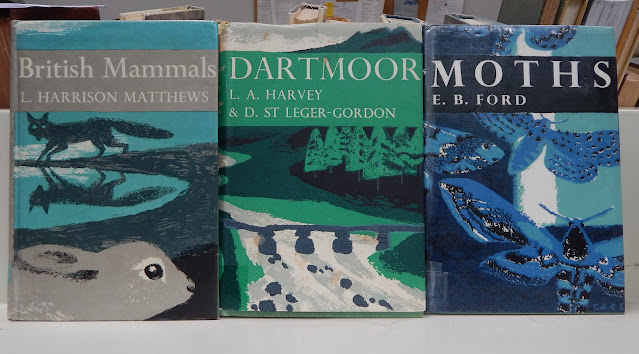

The rest of the board consisted of other experts in their fields (pun intended in some cases): ornithologists James Fisher and Eric Hosking, geologist and geographer L Dudley Stamp, and botanist John Gilmour. The first volume was E B Ford’s Butterflies, published in 1945. A parallel series was initiated in 1948 – the New Naturalist monographs. These were slimmer volumes which concentrated on individual creatures or species. The first of these was by Ernest Neal and took a look at The Badger.

Many well known writers took the opportunity to produce definitive works on the subjects to which they had devoted so much study, including Eric Simms, Oliver Rackham and L Dudley Stamp (he of the editorial board, cheekily assigning himself the odd title). Stamp collaborated with local hero W G Hoskins on a volume entitled The Common Lands of England and Wales. Hoskins is immortalised on the book sculpture you pass as you enter Exeter Library. His Two Thousand Years in Exeter is still regarded by many as the definitive history of the city.

The New Naturalists proved a great success and influenced many a budding biologist. They still grace the shelves of many prominent naturalists, including none other than Sir David Attenborough. They are still being published, and are still known as the Collins New Naturalists, even though Collins itself has now been absorbed into the HarperCollins publishing group. They are now (as of writing) up to number 145, a general volume on Trees by Peter A Thomas. The monographs stalled in 1971 with The Mole by Kenneth Mellanby (a somewhat Moleish name), but given that there is now a volume on Badgers in the general New Naturalist series (number 114) it seems that individual species now warrant their own book length studies. The series was also forward thinking in its addressing of environmental issues, and its acknowledgement of the impact of humanity and modern civilisation on the natural world, as testified by titles such Trees, Woods and Man (with its numbered boles marked for felling), Fish and Fisheries and, most notably, Pesticides and Pollution by Kenneth Mellanby (the mole man).

The New Naturalists are also very popular with book collectors and individual titles can fetch high prices. This is in no small part due to the beautiful artwork created for the dustjackets, which maintained a distinctive sense of graphic continuity between 1945-1985, and which give them such a handsome look when arrayed along a bookshelf. So who was responsible for this much-admired artwork. Well, it was actually two people: Clifford and Rosemary Ellis. And they provide a further link with the Westcountry. Rosemary Collinson met Clifford Ellis at the art school in Regent Street Polytechnic, London where she was studying and he had just started teaching. They married in 1931 and soon began producing work together, sometimes signed C&RE (you can see this signature on some of the New Naturalist covers).

They became well-known for their posters in the 30s, produced for the likes of London Transport (a number for the underground anticipate their NN covers), BP, Shell and the Empire Marketing Board (an organisation also notable for its role in the early years of the British documentary film movement). At the time, all of these organisations gave considerable scope for experimentation amongst the artists they commissioned, and Rosemary and Clifford were able to develop their distinctive style which blended modern and post-impressionist techniques with more representational traditions. We have a book on the posters produced for London Underground down below in the stacks, which we have referred to before in the post on Sybil Andrews and Cyril Power (in many ways parallel figures to Rosemary and Clifford). This includes a lovely spread of 4 posters the Ellises produced, presumably enticing people into the further stretches of Metroland or into the wilds of Epping Forest, all on the outer branches of the tube.

Clifford and Rosemary settled in Bath and both taught art in addition to fulfilling their commissions. Indeed, Clifford became head of the Bath Academy of Art after the war, housed in one of the wings of Corsham Court, an old English country house with sweeping landscaped parklands designed by Capability Brown. This was thanks to the beneficence of the incumbent at the time, the 4th Baron Methuen, himself an artist who had studied under Walter Sickert in the 1920s and was sympathetic to the cause of the arts and art education. Corsham became a renowned centre of art education, with established artists as teachers and famous guest speakers. During the war, the Ellises had already attracted some impressive names to address their Bath Art Club; luminaries such as John Piper, Nikolaus Pevsner (he of the famous Pevsner guides, many of which we have down in the stacks) and Kenneth Clark, former director of the National Gallery and prominent arts broadcaster. His cultural history of the West, Civilisation, was a landmark in television history. With such connections already in place, Corsham was well set to become a significant regional centre for art education. It attracted some prominent post-war artists onto its teaching register, amongst them sculptor Kenneth Armitage, abstract painter Terry Frost, St Ives colonist Peter Lanyon, Ulster painter William Scott and Howard Hodgkin, who painted a portrait of Clifford Ellis.

During the war they had made a number of painted studies of Bath which, although not created under the official aegis of war artists, nonetheless provide a valuable record of the city and the damage it had suffered (which included the Bath School of Art where they had taught). They also played their own part in highlighting the need for some degree of continuity in and preservation of the built environment. Bath would be a key locale in the post-war debates about balancing the needs of modern post-war development and the desirability of maintaining the architecture of the past.

The commission to design the New Naturalist covers gave them an ongoing opportunity to explore the natural world which they loved, and it is the work for which they are now best remembered. They took it very seriously and would do a considerable amount of field research for each book, exploring the terrain and getting a feel for its particularity and atmosphere; or observing the relevant species to get an impression of its habits and behavioural traits. So they would have spent time on Dartmoor in preparation for New Naturalist number 27, written by L A Harvey and D St Leger-Gordon. That’s Douglas, who with his wife Ruth used to live in Sticklepath to the north of the Moor. Ruth wrote a fine study on the Witchcraft and Folklore of Dartmoor, which we have copies of down in the stacks.

They created a sense of continuity within the series with their carefully thought out and meticulously executed design aesthetic. This involved a limited use of colours (never more than 4), a soft-edged, blurry look drawing on post-impressionism, and a stylised, ‘modern’ approach to the representation of animals and plants (with the attention often drawn to the eyes). The soft-edged textures were created by the use of mixed-media – water-based paints, chalk and wax. Sometimes areas of the white paper were left undaubed, blank shapes incorporated into the whole. Considerable visual imagination and intelligence is brought to play in the incorporation of the images within the framework of the cover, and in the way in which they wrap around onto the spine. The series as a whole is a masterclass in the art of book jacket design.

The Ellises continued to design for the series for 40 years, up until Clifford’s death in 1985. The last book bearing their signature style was number 70, The Natural History of Orkney by R J Berry. The use of white space for the curly-horned ram on the front lends it a rather ghostly aspect, with its eye, looking out at the observer/reader, appearing like a patch of mossy lichen. These patches almost resemble a map of the islands, as if the ruminating beast were indivisible from the terrainThe horn extends beyond the frame of the front cover, sweeping in a tentacular curlicued swirl down the spine. Only by taking the book out is its true provenance revealed. The rough waxy background in golden brown gives a good impression of the scrubby clumps of tough foliage covering the terrain. In the thin strip above the title banner, a spectral squadron of seabirds sweeps across a blue-grey bay, their sickle wings like the shimmering arcs of rippling, spume-frosted waves. It’s a fine work to go out on, subtle, spare and hugely evocative of the spartan environment it summons up with such masterful economy and assured style. It’s a work of art which reflects a lifetime of experience, reflected in the confidence to pare things down to a minimum.

Subsequent volumes were illustrated Robert Gillmor, whose clearly outlined style was a necessary departure from the Ellises. It would have done them a disservice to attempt any imitation. The most recent of Gillmor’s covers which we have is for number 93, British Bats which, along with his Caves and Cave Life (number 79), with another flying bat, suggests an affinity for the bold, narrative panels of graphic novel artists. There's certainly a striking immediacy to his work which brings us into close contact with the birds and animals he depicts. He had a longstanding connection with the RSPB, both personally as an active member and as an illustrator. He provided the cover artwork for many of the organizations Birds magazines and, perhaps most significantly, designed the instantly recognisable RSPB avocet logo. Sadly, Gillmor passed away in May of this year, having provided New Naturalist covers for 37 years. Who will take on his mantle and become the third artist and designer for this prestigious series, and what will their signature style be? It will be fascinating to find out.

The Ellises’ collection, including the original artwork for the New Naturalists and work by artists connected with the Corsham school (including Howard Hodgkin's Clifford Ellis portrait), was recently bequeathed to the Victoria Art Gallery in Bath, the city which had been their home for so long. It’s wonderful that their work can now be seen in the public collection there. And it’s wonderful that so many of the New Naturalists, bearing their exquisite artwork, are also available in the public realm – there for you to borrow from your Devon libraries.

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

Comments

Post a Comment