Starstruck: Lord and Lady Lockyer - A Scientific Romance

A while back I was wandering around a churchyard in the tiny village of Salcombe Regis, one of those places which can be found, after some effort, at the end of a narrow, rugged lane to nowhere. A horizontal tomb caught my attention due to the intriguing phrases inset into the stone. It’s not often you find evocative words such as ‘solar observatory’ and ‘stellar physics’ on a grave. A biblical passage proclaims ‘the heavens declare the glory of God and the firmament sheweth his handywork’. A closer examination revealed the grave to be that of Lord and Lady Lockyer. Norman Lockyer (for it is he) gave his name to the astronomical observatory up on the hill above Sidmouth. But how did they both end up in Salcombe Regis. I determined to do some more sleuthing in the stacks to find out.

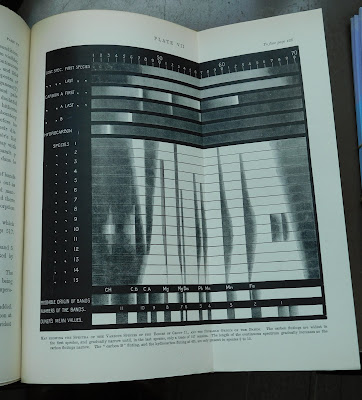

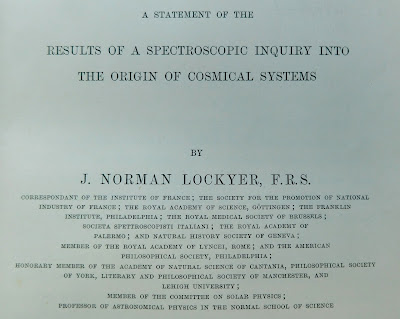

A preliminary look in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, accessible via your library card here, revealed the details of Norman Locker’s life (or Joseph Norman Lockyer, as he was christened). He was born in Rugby on 17th May 1836 and found employment in the War Office of the civil service, which led him to move down to Wimbledon. He had a keen interest in science, something which may well have been passed on from his father and he was something of an amateur astronomer, making observations of the Moon and Mars through a refracting telescope which he purchased and set up in his garden. It was when he moved to West Hampstead with his first wife Winifred and their growing family that he first explored the nascent science of spectroscopy, using it to make observations of the Sun. It was the area of solar spectroscopy which would bring him greatest renown and find his name set down in scientific history books. Spectroscopy involved the study of spectra either from light or electromagnetic emissions, which could lead to insights into the structure of matter, or its chemical components. It might even lead to the discovery of new elements. This is what arose from Lockyer’s observations in 1868. Having determined that the sun had an atmospheric outer layer which he termed the ‘chromosphere’, he analysed his spectroscopic readings and concluded that one band of the spectrum didn’t conform to any known element. Thus it must be something wholly new to human understanding. He named this new element Helium after Helios, the Greek solar deity, and was co-credited with its discovery alongside the French scientist Jules Janssen, who had been carrying out spectroscopic analyses of a solar eclipse viewed from India and coming to the same conclusions. It was this discovery which would lead to Lockyer’s knighthood in 1897.

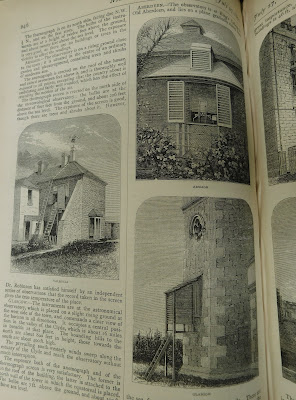

Lockyer became an eminent figure in the scientific establishment of the time. In 1870 he was appointed secretary of a royal commission to further the advancement of science and broaden its educational reach. Those involved in this endeavour were based in South Kensington, where Lockyer’s friend Thomas ‘T.H.’ Huxley would supervise the Normal School of Science from 1881, an establishment which would morph into Imperial College London in the Edwardian period. This was the area where those grand temples of popular scientific education and promotion The Natural History Museum and the Science Museum would be erected. It was in this South Kensington locus for scientific exploration and promulgation that Lockyer set up a new solar observatory, those evocative words which are written on his tomb; and it was in that solar observatory that he first came into contact with Thomazine Mary Browne, a deeply romantic place for the first seeds of romance to be planted.

Thomazine, or Mary as she was familiarly known, would go on to marry Norman in 1903, after the natural end of their respective conjugal entanglements allowed them to finally unite. Mary would also co-author (along with daughter-in-law Winifred Lockyer and ‘with the assistance of’ one Prof. H Dingle) a biography of her husband, The Life and Work of Sir Norman Lockyer, which was published in 1928, 8 years after his death. And yes, we have a copy of it down in the stacks. There’s a lovely photograph of Sir Norman opposite the title page, a calm portrait of the distinguished astronomer taken in later life. He looks out at us through small, wire-framed glasses, hands resting on his walking stick, watch-chain stretching across his tweed waistcoat.

The biography sticks rigorously to Sir Norman’s working life, with Mary largely expunging her own presence and her influence upon him. Chapter 21 begins ‘the year 1903 was one of the busiest, as it was one of the most significant years of Lockyer’s life. She then goes on to quote from a magazine report; ‘As he is at the summit of his scientific fame (said a writer in Men and Women), is about to be married, and in the autumn will achieve the distinction of being President of the British Association, this will be a very great year indeed for Sir Norman’. When it comes to noting that marriage it is done in the most perfunctory manner, and in a dissociative third person: ‘On May 23, Lockyer married Thomasine Mary, the widow of Bernhard E. Brodhurst, F.R.C.S, and younger daughter of Mr. S. Woolcott Browne’.

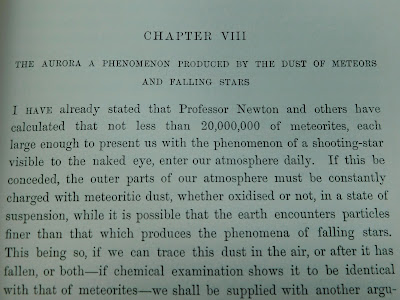

One of the incidents in the life of Norman Lockyer recorded in Mary and Winifred’s biography is the

foundation of the journal Nature, whose first issue was published on November 4th 1869. This was another indication of Lockyer’s fervent desire to communicate the ideas and theories of the scientific worldview to a broader public. In the tank room at Exeter Library, a kind of stack beneath the stacks were a curious assortment of journals, annuals and statistical publications are held, there is a run of bound issues of Nature beginning with the first issue and continuing on into the latter part of the twentieth century. It became the premiere international journal of scientific record, review and education. Mary and Winifred are fulsome in their praise in the biography, hinting that this may be one of Norman’s most enduring achievements: ‘Lockyer’s foresight and power of permanent organisation are nowhere seen to better advantage than in the establishment of Nature. When he built he built to last. Nature has preserved from the first not only its aims and methods but even the details of its outward appearance: the quality of paper on which it is printed and the style of type used are now much as they were in the first issue. The success of Nature owes no little to its name, at once so concise and so comprehensive. This must be admitted, though we may not perhaps be prepared to express the fact in the characteristically enthusiastic language of Sylvester, who wrote to Lockyer in October 1869:

What a glorious title, Nature – a veritable stroke of genius to have hit upon. It is more than Cosmos, more than Universe. It includes the seen as well as the unseen, the possible as well as the actual, Nature and Nature’s God, mind and matter. I am lost in admiration of the effulgent blaze of the ideas it calls forth’.

What a marvellously British sentence, using the word ‘enthusiastic’ in such a damning way, that ‘characteristically’ filled with such withering disdain (or perhaps simply amusement at a friend’s familiar ways). I for one will be using the phrase ‘effulgent blaze’ whenever the situation demands.

The introductory words in that first issue were by Lockyer’s friend T.H.Huxley, popularly (or unpopularly) known as Darwin’s Bulldog for his fierce advocacy of the more mild-mannered scientist’s recently promulgated evolutionary theories. Or rather it is a co-authored introduction, since Huxley begins by quoting from Goethe’s rhapsodic poem Nature in which he embodies the lifeforce as a self-delighting, semi-divine feminine force. It’s interesting that Huxley should introduce this scientific journal on such a mystical, religiose note. We’re a long way from his intellectual descendant Richard Dawkins here. This choice of quotation also suggests that there was far less division between the worlds of the arts and the sciences in this period. Once he has introduced his own voice, Huxley goes on to cite Goethe’s own comments on his intuitively come by paean to Mother Nature: ‘if we consider the high achievements by which all the phenomena of Nature have been gradually linked together in the human mind; and then, once more, thoughtfully peruse the above essay, from which we started, we shall, not without a smile, compare that comparative, as I called it, with the superlative which we have now reached, and rejoice in the progress of fifty years’. Huxley imagines this reflection applying to the new journal: ‘When another half-century has passed, curious readers of the back numbers of NATURE will probably look back on our best, ‘not without a smile;’ and, it may be, that long after the theories of the philosophers whose achievements are recorded in these pages, are obsolete, the vision of the poet will remain as a truthful and efficient symbol of the wonder and the mystery of Nature’. Well, three half-centuries have now passed and Huxley’s insight into the visionary impulse underlying scientific exploration remains potent, particularly as we are seeing further towards distant galaxies and unravelling the subatomic mysteries of matter. The use of spectroscopic analysis of light in astronomical observation, pioneered by Lockyer, is now being focussed on stars many light years away and is helping in the discovery of exoplanets and the nature of their atmospheric make-up. Ultimately, it is revealing planets which have the potential to support life.

The third article in that first issue of Nature is by Norman Lockyer, entitled The Recent Total Eclipse of the Sun. It records his observations on a total eclipse in America. Lockyer explains that ‘an eclipse of the sun, so beautiful and yet so terrible to the mass of mankind, is of especial value to the astronomer, because at such times the dark body of the moon, far outside our atmosphere, cuts off the sun’s light from it, and round the place occupied by the moon and moon-eclipsed sun there is therefore none of the glare which we usually see – a glare caused by the reflection of the sun’s light by our atmosphere. If, then, there were anything surrounding the sun ordinarily hidden from us by this glare, we ought to see it during eclipses. In point of fact, strange things are seen. There is a strange halo of pearly light visible, called the corona, and there are strange red things, which have been called red flames or red prominences, visible nearer the edge of the moon – or of the sun which lies behind it’. Lockyer here works towards his identification of what he termed the ‘chromosphere’, the permanent atmospheric aurora enveloping the sun. As he writes, with barely concealed excitement, ‘what, then, is the evidence furnished by the American observers on the nature of the corona? It is bizarre and puzzling to the last degree! The most definite statement on the subject is, that it is nothing more nor less than permanent solar aurora!’ (Lockyer’s emphatic italics here).

Lockyer became something of an eclipse chaser, travelling far afield to America, Spain, Sicily, India (on a Government Eclipse Expedition in 1871), Spain, Greece, and Lapland (as it was then known). His last expedition, to Palma Majorca in 1905, was unfortunately spoiled by obscuring cloud cover. Still, he got to stop off at Innsbruck on the way back for the International Meteorological Conference. His eclipse reports and the conclusions he drew from his observations are peppered throughout the Victorian issues of Nature. They are also gathered together in a 1900 volume called Recent and Coming Eclipses, which combines travel writing with scientific observations. For example, Lockyer recounts his travels to Lapland to view the 1896 eclipse. ‘During the three-quarters of an hour steaming from the ship they encountered a sharp squall, which would have saturated everybody if it had not been for the invaluable sou’-westers and oilskins; and it is well here to note that if one goes to the north of Norway, these should always be found in the kit together with a pair of sea-boots. The party landed, however, safely on a small island on the eastern shore of Bras Havn, and commenced immediately to put up tents. By 11pm local time, all preparations were finished. The evening turned out so beautiful that a chat round the camp fire and a drop of grog were indulged in before turning in’.

It was on his eclipse-chasing travels that Lockyer began to take an interest in ancient sites – Greek and Egyptian temples, stone circles and rows – and their possible alignment with the annual cycles of sun and stars. He brought such speculations closer to home with his investigations of British megalithic sites. The December 14th issue of Nature from 1905 includes his Notes on Stonehenge pertaining to Folklore and Tradition. He writes that ‘tradition and folklore, which give dim references to the ancient uses of the stones, show in most unmistakeable fashion that the stones were not alone; associated with them almost universally were many practices such as the lighting of single or double fires in the neighbourhood of the stones, passing through them and dancing round them; there were also other practices involving sacred trees and sacred wells or streams’. Lockyer also observes some of the Cornish stone circles and sites in articles published in Nature in 1906, noting that ‘my wife and I visited the region in January, 1906, but previously to our going Mr Horton Bolitho, accompanied by Mr Thomas, whose knowledge of the antiquities is very great, had explored the region and taught us what to observe’.

Lady Lockyer not only accompanied him, but also took photographs of the megalithic sites, which were used for the articles and in the subsequent book. We can imagine them setting up their respective tripods near the stones, affixing their cameras and theodolites atop. All of these observations, with their central thesis of the solstitial alignment of neolithic sites for sacred ritual observance, were collected in Stonehenge and Other British Monuments, which is amongst the Lockyer books down in the stacks. It has some splendid charts mapping Lockyer’s theodolite measurements and includes a chapter on ‘The Dartmoor Avenues’, or stone rows. In the pointed introduction, Lockyer comes across as something of an antiquarian too: ‘In continuation of my work on the astronomical uses of the Egyptian Temples’, he writes, ‘I have from time to time, when leisure has permitted, given attention to some of the stone circles and other stone monuments erected, as I believed, for similar uses in this country. One reason for doing so was that in consequence of the supineness of successive governments, and the neglect and wanton destruction by individuals, the British monuments are rapidly disappearing’. Such a confluence of modern scientific method with ancient customs and megalithic sites brings to mind cult 70s SF series like Nigel Kneale’s Quatermass (with its Ringstone Round song) and the Avebury-set Children of the Stones.

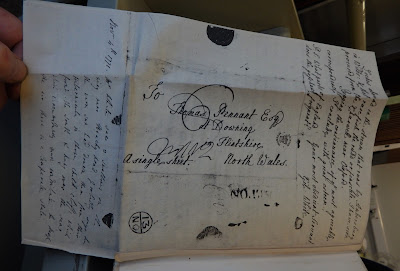

It was in a 1922 edition of Nature that Mary put out a request for information on her late husband for the biography she was then preparing. That biography was to be ‘in a form which I hope will make it not only of interest to his many friends and admirers, but also a contribution to the scientific literature of the present day. If any readers of Nature happen to possess letters from my husband, I should be greatly obliged if they would give me the opportunity of seeing them. My object in making this request is that any matters of general interest which thereby come to light might be incorporated in the work’. In the end, a main section of general biography was followed by essays on various aspects of Lockyer’s work and its legacy, including: The Constitution of the Sun: A Modern View by C.E.St John; The Story of Helium reprinted from Natureof Feb 6th and 13th 1896; Dissociation Equilibrium by M.Saha; The Meteoric Hypothesis and Stellar Evolution by H.Dingle (something of a misstep by Lockyer here); Education and National Development by Sir Richard Gregory; and, best of all, Sir Norman Lockyer’s Astronomical Survey of Egyptian Temples and Ancient British Stone Monuments by Rev. J Griffith. It's always good to see an antiquarian vicar investigating the ancient mysteries.

Whilst the biography focusses almost exclusively on Lockyer’s work and scientific career, as we’ve have seen, a few interesting glimpses of his personal life and range of extra-scientific interests come through. Perhaps surprisingly, we learn that ‘one of Lockyer’s most valued friendships was that of Tennyson, whose house he appears to have visited for the first time in January 1878, although a fairly intimate friendship between the two men had existed for some years. They were admirably suited to one another, for while their main interests were complimentary, each was at home in the intellectual sphere in which the other excelled. Lockyer was able to appreciate an aspect of Tennyson that was hidden from those whose interests were confined to pure literature; he recognised how accurate a knowledge of natural phenomena and the existing trend of scientific thought the poet possessed’. On a similarly literary front, we learn that ‘on the occasion of Mark Twain’s visit to England in June (1907), Lockyer invited his old friend to luncheon at Pen-y-wern Road, and a pleasant and entertaining function took place’. Sometimes you can read between the lines of the dry relation of events. For instance, we are told of ‘the address (as President of the British Association) on “The Influence of Brain Power on History” was delivered to a large audience on September 9 (1903)...The address met with a very varied reception from the press of the country, so far as the arguments were concerned, but with regard to its forcefulness there could be no question. It was discussed in two hundred leading articles, the great majority of which were favourable, although the criticisms were in some instances very severe’. The Influence of Brain Power on History is a marvellous title in and of itself, no matter the substance of what ensued. The same might be said of his book The Meteoric Hypothesis (a contentious volume) which boasts some spectacular chapter titles.

We gather that in 1900 ‘he spent part of his summer holiday at Westgate-on-Sea with some of his family. He had not been there for some years and greatly enjoyed re-visiting the place’. In the following spring of 1901, ‘together with (F.C.) Penrose he conducted an examination of Stonehenge...and found strong evidence for regarding it as a solar temple’. Later, ‘in May 1905, an opportunity occurred to visit Cornwall, and with Lady Lockyer and a number of local helpers he inspected some of the ancient monuments of that county. The “Hurlers” were first examined, and some later stones in the Penzance district. The interest and co-operation of Lord Falmouth were secured, and with his permission a gap was made in a hedge which prevented the sight of “The Pipers” from “The Merry Maidens”. The result of the measurements taken was highly satisfactory in establishing the main principles of Lockyer’s hyphothesis (that the Hurlers formed a star temple constructed on a principle similar to that previously found in Egypt), and revealed an extensive programme of observations which would have to be carried out in order to fill in the details”.

Perhaps it was this area of work which led to one of the more unusual, extra-scientific honours bestowed upon Lockyer. In 1907, ‘after his visit to the Lakes (including Keswick, where he took measurements of the circle), (he) went to Swansea to attend the Gorsedd. Here there was conferred on him the degree of Ovate, with the title “Gwyddon Prydain”, meaning “Britain’s Man of Science”. Among the congratulations which he received on this distinction was one from Roscoe, with a letter in which he said that Rücker, whose knowledge of Welsh was remarkable, had told him that Lockyer’s correct English designation would thereafter be “Your Solar Prominence”’. So Lockyer became a science druid!

It’s a shame that in her biography of her husband, Mary Lockyer rendered herself so invisible, and identified herself in connection with her male relatives, since she was a remarkable person in her own right. She went to Queen’s College in Harley Street, an establishment intended to give a broad education to governesses so that they could pass some of it onto their charges. This was not the course which Mary took, however. She continued her studies, with the aid of a scholarship, and pursued her interests in science, including astronomy. She also studied applied mathematics and physics at University College London in the Bloomsbury area. Needless to say, this was not an educational path generally deemed fit for women, so she was definitely going against the grain.

This rebellious spirit was further displayed in her activism in the cause of women’s education and suffrage and social activism in general. She had worked, with her sister Annie Leigh Browne, at Toynbee Hall, the institution set up by Canon Samuel and Mrs Henrietta Barnett in Commercial Road, Spitalfields to bring education to the working class poor of the area, provided by students and teachers at nearby universities and colleges, bringing together people from diverse backgrounds with the ultimate aim of fomenting social change. We have come across Toynbee Hall before in our post about William James Ashley, the Boy From Bermondsey.

Mary and Annie became involved in the push towards setting up accommodation for female students in the city, a vital step establishment of women’s education. As the obituary for Lady Lockyer in the issue of Nature from October 9th, 1943 puts it, ‘they were the prime movers in the establishment of the hall of residence for women students in London. An appeal was made for funds to provide such accommodation for women students at University College and the London School of Medicine for Women, and in 1882 the Misses Browne (Browne was Lockyer’s maiden name) took the lease of a house in Bloomsbury for a term of twenty-one years and placed it at the disposal of a committee appointed to carry out the project. The first student to come into residence was Miss Cicely Ullman...and the house was soon full. It became clear that a real need had been met and that further accommodation was required. Two adjoining houses were afterwards leased, but when the lease terminated it was decided to build a College Hall in Malet Street on a freehold site and large enough to accommodate 112 students. The foundation stone of this Hall was laid in October 1931, when Lady Lockyer gave an address on its origin and growth’.

Mary pursued her own scientific interests in further education with the aid of a scholarship, choosing natural philosophy (basically the natural sciences, or natural history) and astronomy as her favoured subjects. This was what brought her to the Solar Physics Observatory, and into the orbit of Norman Lockyer. Such intellectual pursuits were uncommon for women at the time, and the educational establishments certainly did not encourage their participation. In 1923, she became one of the first women to be elected a fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society, only a few years after women had first been admitted to that august institution.

Mary and her sister were also both active in the suffrage movement in the late nineteenth century and the early years of the twentieth century. She was for a time treasurer of the Women’s Local Government Society, the organisation which grew out of the Society for Promoting the Return of Women as County Councillors, the latter established in 1888 by a group of women including her sister Leigh. Its aim was to get women elected to local councils, which they’d perceived was possible due to an 1888 Local Government Act which didn’t explicitly exclude women from standing for positions in the newly formed county councils. She brought her suffragist activism down to the westcountry when she moved there with Norman, and a branch of the National Union of Women Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) was set up there. From its establishment in 1909 up until 1918, Mary acted as its secretary.

The active nature of her involvement in the suffrage movement is indirectly reflected in an article she wrote for Nature magazine, published in the January 10, 1907 issue. This was a review of a book on jujutsu (better known as jujitsu), The Fine Art of Jujutsu, written by Mrs Roger Watts (Emily Diana Watts, in fact). It was the first book on the subject to be published in English. This Japanese art of wrestling had been recently demonstrated in Britain, and almost immediately taken up by Edith and William Garrud, who trained in the art and then began teaching it themselves. Diana Watts (as she preferred to be known) studied under the same teacher as them, Sadakazu Uyenishi, and also took up teaching. Edith was a dedicated suffragist and joined the Women’s Freedom League in 1906. It was at this point that she started to teach jujitsu as a form of self-defense for women. She would go on to train the members of the WSPU (the Women’s Social and Political Union) in the art, having been invited to do so by Emmeline Pankhurst in 1909. This led to the press coining the term suffrajitsu, a mocking term which could be transformed into a badge of honour.

Jujitsu was a particularly effective response to the brutality of policemen and jeering onlookers at demonstrations since it used the strength of the attacker against them. In her article, Mary Lockyer describes its principles thus: ‘In jujitsu it is a question of quickness and brains; the throws are given by taking advantage of the opponent’s movements, so that as the attacker advances the opponent trips him up, or gives the throw, by profiting by the momentum of the attacker’s body, placing his foot, leg, or arm in such a position that the attacker cannot save himself from falling. In fact, the momentum of the attacker is used to his own detriment’. So, an art (or, given that this is a review in Nature, a science) which uses keen observation and quickness of wit against the arrogance and assumed physical superiority of brutish strength. Lockyer seems to demonstrate a practical knowledge of the art in her informed comments. She writes ‘perhaps the most difficult throws are those given in figs.44 and 45, which are here reproduced, called the ‘Uchimata,’ for it requires immense practice to get the balance necessary to gain the second position. Besides the throws, there are many locks which are most effective in overcoming an opponent. Fig.111 and the following series represents one of these in detail, by which, when used in self-defense, it is not difficult to break the elbow of the attacker’. From which, I think it is safe to assume, Lady Lockyer was an experienced practitioner of the art of suffrajitsu.

Lady Lockyer was also instrumental in the establishment of the observatory above Sidmouth, now known as the Norman Lockyer Observatory. Sir Norman had been disappointed (to put it mildly) at the relocation of the Kensington solar observatory to Cambridge. He and Lady Lockyer had moved down from London to the south west in the early years of the twentieth century, beginning to build their ‘Brownlands’ house on the slopes of Salcombe Regis from 1909, and it was here that they decided to build a new observatory. Mary had childhood roots in the area through her maternal grandparents and had inherited land, upon which they had built their new home. As the biography of Norman Lockyer notes, ‘the land belonging to Lady Lockyer on which the house was built at Salcombe Regis, near Sidmouth, was exceptionally suitable as a site for an Observatory, and thanks to the generous offer of £9000 by Mr.F.K. (now Sir Francis) McClean, of £5000 by Sir Norman and Lady Lockyer, and of five acres of land and material for building by Lady Lockyer, he felt encouraged to discuss the matter with his friends, and further financial help being offered, he decided to establish a new observatory’. The first observations from the new observatory were made in 1913, and after an almost immediate shutdown occasioned by the war, re-opened in May 1919. From here, Lockyer could continue his solar spectroscopic observations which he had so assiduously pursued over his lifetime.

Initially known as the Hill Observatory, it became the Norman Lockyer Observatory after his death in 1920, a fitting memorial. Lady Lockyer continued to be closely involved in its running, remaining its honorary treasurer until her death. She was in some senses its guardian spirit, welcoming the scientists who came down to use it, paying host to them and undoubtedly discussing scientific matters with them with informed knowledge and understanding. She ensured its continuance after her death too. The Nature obituary notes ‘she has bequeathed to the Observatory Corporation the freehold house at Salcombe Regis in which she and Sir Norman lived, and most of its contents, as well as about forty acres of land up to the summit of the hill on which the Observatory stands, and a farm of eighteen acres and a cottage’. R.A.Gregory, the author of the obituary, goes on to note, rather pointedly, ‘it is rarely that such substantial benefactions are made in Great Britain for the advancement of astronomy, though they are common in the United States. They ensure permanent provision for purely scientific research at a time when attention is chiefly concentrated on investigations of possible industrial or other practical value. All who are interested in the pursuit of knowledge and the intellectual expansion produced by it will pay grateful tribute to the spirit and service by which Lady Lockyer used her faculties and means with wisdom and social understanding, not only during her life, but also provided for the continuance of this influence after she had passed into silence’. What a lovely phrase.

And the library has reason to be thankful to her as well. That reference to ‘most of the contents’ of the Salcombe Regis house presumably excludes a good number of books from the Lockyer library. Many of them have ended up down in the stacks here at Exeter, their provenance denoted by an Exeter City Library bookplate with gothic lettering declaring the book in question to have been ‘bequeathed by Lady Lockyer, Sidmouth A.D.1943. A number of the books cover her favoured subjects, astronomy and botany. There are several of her husband’s works, including Recent and Coming Eclipses (of which the latest anticipated was 1905, which Lady Lockyer travelled to Majorca to view), The Sun’s Place in Nature and Chemistry of the Sun. Interestingly, the copy of Chemistry of the Sun, published in 1887 and so central to Sir Norman’s scientific work, has a bookplate adjacent to hers. It is that of Bernard Edward Brodhurst. He was an eminent orthopaedic surgeon whom Mary married in 1885. Some years her senior (he had already outlived two other wives) he died in 1900, and she married Sir Norman shortly thereafter. Brodhurst had been on the Committee for College Hall, so they must have struck up a relationship at the time she was campaigning for this. The fact that this book was evidently in her collection from the time of her previous marriage shows that her connection with Lockyer, established at the Kensington solar observatory, remained, as did her fascination with astronomy. The bookplate might have been Brodhurst’s, but we know who the book really belonged to.

Lady Lockyer’s interest in botany and the natural sciences is also reflected in some of the books she bequested. She had published a short piece in the January 16 1913 issue of Nature titled Precocity of Spring Flowers in which she wrote ‘many references are being made to the number of plants in flower now to be found in various parts of the country. May I give a list of those I gathered on January 6 in our garden in South Devon, ranging from 230 to 500 ft above sea-level?’ She proceeds to do so, showing an acute knowledge of flowers and their specific varieties in the process. In the special collections in the cage folio (where many precious things can be found) we have a couple of lovely large illustrated books from Lady Lockyer’s collection from which such knowledge may have been gleaned. They are the sort of books whose exquisitely engraved and coloured pictures are covered by thin protective sheets of tissue paper. The Genus Iris by W.R.Dykes was published in 1913 and British Flowering Plants by Professor Boulger, with illustrations by Mrs Henry Perrin, was published in 1914 by Bernard Quaritch. Quaritch was a renowned antiquarian bookseller who ventured into publishing. He is a fascinating character in himself and a potential subject for a future blogpost, since we have a number of books in the stacks which relate to him. There is also the two volume Trees and Shrubs of the British Isles, Native and Acclimatised by C.S.Cooper and W.Percival Westall.

Elsewhere we find a 1904 volume with a compendiously descriptive title, viz. ‘Precious Stones: A Popular Account of their Characters, Occurrence and Applications, with an Introduction to their Determination, for Mineralogists, Lapidaries, Jewellers, etc. With An Appendix on Pearls and Coral’. It has rather splendid outline keys on the tissue paper which act as unobtrusive labels for the coloured illustrations. There is a lovely 1900 edition of Gilbert White’s Natural History of Selborne, a classic of nature writing, which includes many engraved illustrations as well as a foldout facsimile of one of the good parson’s letters.

The Lady Lockyer collection goes beyond the bounds of the sciences. As we have seen, both she and Sir Norman took an active interest in all aspects of the world. One particularly beautiful set of books is the Japanese Temples and Their Treasures art folios. These are sets of prints loosely housed within fabric covers with decorative embossing, tied together at the edges by several lengths of linen. There is also a two volume set of Henry Stanley’s 1885 account of his explorations, The Congo and the Foundation of Its Free State, which comes with a fold-out map of the terrain. This may well have been of interest when planning a West African eclipse-watching trip.

This bequest is of great signifcance to the library’s collection, and shows the degree to which both Lord and Lady Lockyer were committed to the furtherance and communication of human knowledge and understanding of the world. They looked outwards to the stars but they were also concerned and engaged with their fellow humans. The journal Nature was Sir Norman’s way of communicating his own excitement and wonder at the world, and the universe about him, his joy in the intellectual (and emotional) process of unfolding discovery. That this, and the many books bequeathed by Lady Lockyer, are available for all to explore and learn from in a public library seems a fitting continuation of the lifelong endeavours which both tirelessly engaged in to bring education and enlightenment to all, regardless of race, class or gender. Theirs is a twinned stellar spirit whose light shines on.

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

Comments

Post a Comment