William and Evelyn de Morgan - A Marriage of Art and Life

With the opening this weekend of the new William de Morgan exhibition at RAMM (the Royal Albert Memorial Museum) it seemed an opportune time to delve down into the stacks to see what I could discover about the renowned potter and ceramicist, so closely associated with William Morris, the Arts and Crafts movement and the whole Aesthetic, er, aesthetic of the fin de siecle. I was aware that we had the book The Cult of Beauty on the shelves of the main library floor. This was published to accompany the V&A exhibition of 2011 which explored the many facets of the Aesthetic movement, and which included examples of William de Morgan's ceramic tiles which were such an essential part of any discerning aesthete dandy's interior decor.

What I didn't realise was that William de Morgan was a novelist as well as a potter and ceramicist. Indeed, he was better known for his writing in his time, Joseph Vance in particular being a huge success. Although it is often regarded as a classic Victorian novel, it was actually published in 1906. By this time, de Morgan's ceramics business had folded, and writing was a new creative direction for him. Given his supreme reputation as a central artist in William Morris' circle, it is surprising to learn that financial success and stability only came late, and was achieved through his writing. Joseph Vance: An Ill-Written Autobiography is a picaresque everyman story, with the titular character making his way through life, his progress viewed from childhood to old age. His assiduous, hard-won position contrasts with his father's more instantaneous leap from working class penury to living the life of reilly, which he happens upon through a mixture of luck and low cunning. The novel is also notable for two strongly written and richly characterised female characters, Lossie Thorpe and Janey Vance, who play a central role in Joseph's growth to maturity. The children's writer, poet and socialist Edith Nesbit wrote an admiring letter to De Morgan, telling him 'your book is a beautiful book, wise and witty and tender. I believe it will be living and beloved when most of our present-day novelists are dust and their works have perished with them'. It didn't quite work out that way. De Morgan's living legacy turned out to be his ceramic and pottery art. Such praise from a writer of Nesbit's calibre suggests the novel may be worthy of rediscovery, however. De Morgan's narrative of ordinary life, combined with a mildly satirical element and a belief in female emancipation, seems very reminiscent of the novels H.G.Wells wrote during this period, with similar success. Kipps, for example was published a year earlier in 1905. Also like Wells, De Morgan had a socially progressive outlook, attitudes which drew very much on the strong beliefs of his wife, the artist Evelyn de Morgan. It may well have been Evelyn who prompted him to take up writing, too, in part to lift him out of a deep depression in the wake of the closure of his pottery business. She had found a couple of chapters of a novel which he had thrown away some time ago, but which she had set aside. She now placed them by his bedside, along with a pencil, and said to him 'I think something might be made of this'. It was a gentle hint which was taken up, and which led to his secondary career - a very successful one.

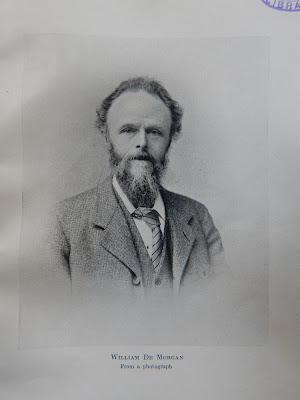

I discovered a biography of William de Morgan down in the stacks, elegantly bound in red leather. Actually, this 1922 biography by A.W.Stirling is a dual one, combining the lives of William and Evelyn de Morgan. This is appropriate enough given the closeness and mutual supportiveness of Evelyn de Morgan and her husband William, whose initially unsuccessful pottery business she kept afloat for many years through moneys earned from her own art. Evelyn painted mythological and spiritually themed canvases in a symbolist style, the subjects generally female. Her exhibitions in the 1880s and 90s brought her many accolades, with arch-late Victorian artist G.F.Watts declaring her to be 'the first woman artist of the day - if not of all time'. She was also a suffragist and pacifist, strongly opposed to the Boer and first world wars. Her work in the twentieth century sometimes addressed these beliefs, with strong anti-war sentiments expressed in paintings such as The Red Cross. Her entry in the scrupulously level-headed Oxford Dictionary of National Biography ends on a not of high praise: 'Her enduring reputation as an artist of extraordinary imagination and ambition was anticipated in an obituary written in 1920: "it is safe to prophesy that Evelyn de Morgan's works will be eagerly sought after as some of the Old Masters are today"'. Again, such a state of affairs may not as yet have come to pass, but her work is definitely now finding its place amongst the more well-established male artists of the Pre-Raphaelite, Aesthetic and Symbolist movements.

William de Morgan's mother was also a strong, individualistic woman who refused to conform to the conventions of her age. She had tutored the similarly rebellious and intellectually daring Ada Lovelace, who worked with Charles Babbage on his analytical engine and is now thought of as a pioneer of proto-computer programming, a woman truly ahead of her time. William de Morgan bore the name Frend as his middle name, a recognition of his mother's lineage - Frend was her maiden name. It's disappointing, then, that this dual biography is entitled William de Morgan and his Wife. I suspect both Evelyn (who died three years before its publication) and William (who died two years before Evelyn) would have had something to say about that insulting omission. It's surprising to discover, then, that the author was Anna Maria Stirling, Evelyn's sister. She may have been adhering to the conventions of the time, and had, of course, grown up during the Victorian era. Perhaps we should give her credit for granting her sister equal status within the pages of the book itself. Certainly there are many more plates of Evelyn's work than there are of William's. This no doubt in part reflects the higher status William enjoyed as an author at this point in history.

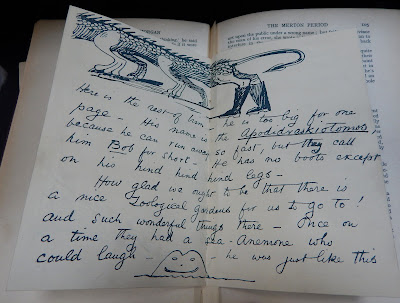

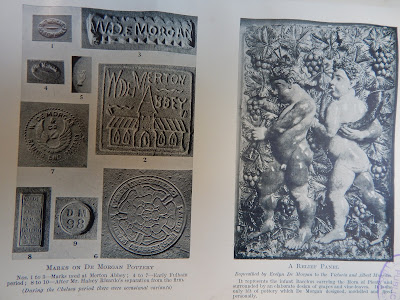

The biography includes some charming and touching details. Inserted in one chapter is a facsimile of a letter William sent to a young niece, complete with cartoons of an elf and a fantastic dragon-like beast which, as he points out, is simply too gigantic to fit onto one page. This points to William's light, playful nature. He was fond of puns and the biography features many of his amusing creature doodles as marginalia. These are reminiscent of the cartoons which Edward Burne-Jones produced of his dear friend William Morris - both men were also close friends of De Morgan. The doodles suggest a similarly tender-hearted and affectionate nature. Dragons and fantastic beasts were an abiding visual interest and turned up on a number of pottery and tile designs. The composite monogram printed at the beginning of the biography is also a lovely and strikingly modernistic design. It seems to represent their indivisibility, their marriage a mutually supportive partnership of life and work. The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography phrases it in a lovely way: 'It was a childless marriage, but successful; they laughed at each other a lot, and she strengthened his resolve'.

The pots and tiles whose alluring design, patterning and light-catching sheen are the focus of the RAMM exhibition are inextricably linked with William Morris and the Arts and Crafts Movement (although perhaps the exhibition is a step towards extricating them from this reflexive association). De Morgan had met Morris and Edward Burne-Jones in the 1860s, and it is thought that it was Morris who was the prime influence in redirecting his focus from painting to the decorative arts of tile and stained glass design. It was the former which he soon began to concentrate on. He set up kilns in Fitzroy Square, a location later to become a locus of the Bloomsbury set, and when that met an unfortunate end (he burned the roof down) in that arch-Pre-Raphaelite neighbourhood, Great Cheyne Row in Chelsea. In 1882, he relocated to a larger workshop in Merton Abbey in South London, following in the footsteps of Morris. It was a move which underlined how closely their endeavours and artistic outlooks were aligned. It was after he moved his base to Fulham, which was nearer to home, that his work can probably said to have reached its peak, however.

The business stuttered and lost momentum as the new century dawned, but it had by then flourished for a good few decades - a not inconsiderable achievement for such a small and personally guided outfit. His work went out of fashion in the first half of the twentieth century, but a revival of interest in the second saw him gradually elevated to the status of a major artist of the Victorian period. He was particularly emblematic of the age in that he combined an artistic sensibility with a scientific curiosity which saw him experimenting with the chemistry and physics of firing and glazing. The resulting lustre of his ceramics and tiles could seem truly alchemical in their magical transformations from the raw material fed into the kilns. The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography suggests that 'the appeal of De Morgan's pottery lies in his glazes, which are richer and softer than those of his contemporaries; in his skill with colour - his one time partner Halsey Ricardo wrote of "the pools of colour into which one can dive and scarce plumb the full depth"....and in his decorative handling of birds, animals, and fish, some from nature, others from the comic bestiary of his own imagination'. The RAMM now offers the opportunity to dive into those lustrous colours and delight in the fantastic designs.

Perhaps we should leave the last word to the author of the Preface to Anna's biography of her sister, one Sir William Richmond, R.A., who styles himself 'An Old Friend'. 'It is unusual to find two people', he writes, 'so gifted and so entirely in harmony in their art, who acted and re-acted on each other's genius. Their romance is one before which the pen falters: but which, nevertheless, was an abiding factor in all they have left to the world: and Sir Edward Poynter, P.R.A., looking after De Morgan and his wife one day, as they left his beautiful garden, epitomized the impression created by their presence. "There", he said, "go two of the rarest spirits of the age".

Comments

Post a Comment