Bernard Quaritch's Big Book Of Books

Right at the beginning of the Dewey decimal system you will come across books about books – bibliographies, library histories, publisher’s tales and so forth. It’s perhaps not surprising that a librarian such as Melvil Dewey should make books themselves the foundation of his rationalised catalogue system. If he wanted a really firm foundation in a more literal sense, he could do worse than prop the whole edifice up on two of Bernard Quaritch’s General Catalogues of Books. These certainly stand out on the bottom shelf of the books on books section of the stack. There they are, two volumes bound in red leather with gilded lettering. They are almost comically broad, and I would warrant are the widest books in relation to their height that are to be found in the stack collection. Bernard Quaritch’s General Catalogue of Books, the gold letters declare, easily fitting in on a couple of horizontally spaced lines. The publication dates are embossed at the base – London 1874 and London 1877. The second volume is subtitled The Supplement 1875-1877. Evidently the 44, 324 entries of the first volume, which listed about 200, 000 books, was insufficient to encompass the full range of Quaritch’s collection, and an addendum was required. This was all highly impressive, and led me to think ‘who is this Bernard Quaritch fellow’? Some further sleuthing in the stacks was clearly called for.

I turned to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, a compendious set running to over 50 volumes which can be found in the reference section of the stack. The sizeable entry on Quaritch made his eminence in the Victorian bookselling world clear. Indeed, he was sometimes referred to as the ‘Napoleon of Booksellers’, a somewhat backhanded compliment which alluded to his dominant and all-conquering presence at any sale of the private libraries of eminent collectors.

Born in 1819 in a small village in the German province of Thuringia, he was set on making his way in the world of bookselling from an early age. He served an apprenticeship with a local bookseller from the age of 15-19 before heading for Berlin in 1839 where he found more work in the book trade. In 1842 he emigrated to London, where he was employed by Henry George Bohn, the pre-eminent bookseller and publisher of the time. An ambitious and strong-minded person, he always intended to set out on his own as soon as he could, and this he did in April 1847. Never one for false modesty, he declared his intention to become ‘the first bookseller in Europe’. In these early years of establishing his business he needed a little extra income, and he gained this from journalism. He found support in this regard from two fellow Germans (who would soon become fellow immigrants in London) who set up a radical newspaper called the Neue Rheinische Zeitung in 1848 to reflect the revolutionary movements then active in the country. Quaritch was briefly an overseas correspondent, sending his work over to those founding editors – two fellows called Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels – in Cologne.

From humble beginnings in a Leicester Square premises he gradually built up his business and his reputation for tracking down obscure tomes for bibliophile seekers. The reach of his stock was global and spanned many languages. Oriental literature was a particular fascination and specialty. In the 1874 catalogue the Oriental Literature section runs from pages 633-795. It is titled ‘Bibliotheca Orientalis: a Catalogue of Eastern Literature, including works in the languages of Asia, Africa, and Polynesia; and upon the HIstory and Geography of those regions of the globe; from the libraries of Flugel, Caussin de Perceval, and other Scholars and Collectors’It includes sections for Iranian language books in Zend, Persian and Afghan; Turanian and Mongol literature; Armenian and Osetic language books; and books in Telugu, Canarese and Malayalim. Many of these definitions are now historic. A random sample includes: A Commentary on the Pentateuch by Rabbi Levi ben Gerson (c.1476 ‘very rare – it is one of the first Hebrew books ever printed’); Buddhaghosha’s Parables: translated from the Burmese with an introduction containing Buddha’s Dhammapada or ‘Path of Virtue’; Adventures of Aboo Zyde of Surooj, in Fifty Stories, by Aboo-il-Kausim-ool-Hureereeyo, with an Arabic-Persian Dictionary of all the terms in the work; and Dutril’s Dictionnaire des Hieroglyphics of 1839, about which Quaritch comments ‘it is a pity this delightful work was never finished. Its learned and caustic author makes minced meat of the luckless Champollion’. Champollion’s works on Egyptian hieroglyphs are, however, also available in the catalogue. In comments like these, we get a sense of Quaritch as a man who took pride in his learning and who had no compunction in stating his informed opinions in the strongest terms.

These immense catalogues are in part a display of his considerable knowledge of books, the appended comments to many of the volumes making it clear that he appreciated their intrinsic value in contributing to the sum of human knowledge as well as their financial worth. His admiration for Arabic literature comes across in such comments, some of which are lenghty summations of the work in question. Of Ibnu ‘L-Athir’s 12 volume Chronicon Quod Perfectissimun inscribitur, he writes ‘it has taken twenty years to publish the text of this highly important work, the greatest historical composition of the Middle Ages. Ibnul Acir is not only superior to all similar authors amongst his coreligionists...but also to the Christian chroniclers. No work upon the Crusades can be properly written without almost perpetual reference to the pages of the Kamilu ttawarikh'. These are the sort of volumes buyers at the British Museum or Library would have pounced upon.

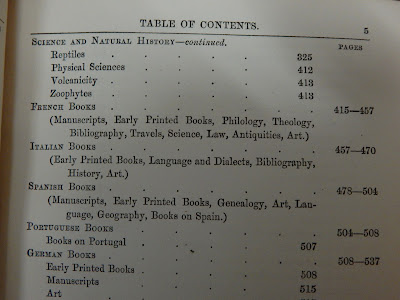

Quaritch’s classification system in his catalogues is throroughgoing and comprehensive, with many subcategories branching off from the main subject areas. It’s interesting to note that the 1874 catalogue predates the first publication of Melvil Dewey’s library classification system by two years. The Dewey Decimal System is still the standard for library cataloguing, and Quaritch’s own catalogues can be tracked down in the stacks under the number 017.4. Quaritch’s categories include a good number of oddities, some of which have the musty air of antique obsolescence. Early on we encounter the subject of Steganography. I had no idea what this meant, so looked it up and discovered it concerned the art of cryptography or secret codes, of the various means of disguising or hiding messages or information within seemingly ordinary material. How terribly intriguing.

I suspect Quartitch rather looked down upon popular writing, on the kind of stories which appeared in the many journals and magazines which flourished in the 19th century (some of which we have down in the stack cage - Blackwoods Magazine, Dickens’ All the Year Round and The Strand, for example). He does spare a little space for ‘Fiction, Romances and Popular Books’ however. These are subdivided into Fables; Grotesque Stories, Apologues; Oriental and Fairy Tales; Proverbs; Religious Works, Dance of Death etc; National Traditions, Legends, Ballads; Medieval Popular Science; and Epic Poets.

When it comes to Sciences, Natural History, Engineering etc., we find subcategories for Conchology and Mollusca, Ichthyology, Infusoria (an old term for freshwater microorganisms which would have been revealed by new microscope observations), volcanicity and ‘zoophytes and addenda’. The supplement broadens the scope of the category to a slightly provocative degree, adding Alchemy, Music and Horology. Alchemy would probably be better suited to the categories of Religions, Mythologies, Philosophy, Mental Aberrations. Mental Aberrations! That surely invites further investigation.

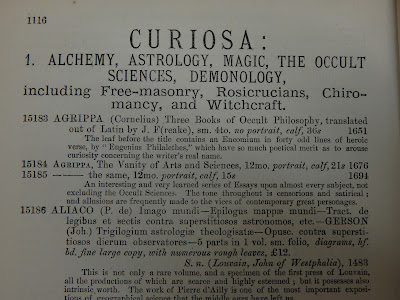

These categories incorporate Occult Sciences, which brings us to the realm of the M.R.James ghost story; of his antiquarian seekers who ignore those warnings to the curious and uncover that which it would’ve been best to leave undiscovered. In the supplement, the categories have been slightly altered, now covering Worships, Metaphysics, Occult Sciences, Demonology with an addendum noting that this includes Freemansonry, Rosicrucian, Chiromancy (palmistry) and Witchcraft. Another category in the Supplement goes under the splendid name of Curiosa. This includes the subcategories of Alchemy, Astrology, Magic, Chiromancy, Rosicrucians, Freemasonry; Secret Writing (that would be Steganography again, I suppose); Proverbs; and Legends, Mythology, Folk-Lore.

Quaritch is evidently acquainted with such Curiosa himself, judging from his comments on a book from 1801 by one F Barrett entitled The Magus: or Celestial Intelligencer, being a complete system of Occult Philosophy. This includes ‘portrait and numerous curious plates and other engravings, some coloured, magical and cabalistical figures etc’. Quaritch notes that this is ‘a very strange and singular work by an adept, fully answering to its title as a complete system. Nowhere else are the practical details so fully entered into’. Beware, Mr Quaritch, beware. Some knowledge is best left hidden.

Quaritch also gives us his tuppenceworth on a book in the section on Gipsy, Thieves’ and Jews’ Slang. The volume in question is George Borrow’s Romano Lavo-Lit: Wordbook of the Romany, with many pieces in Gipsy, Specimens of their Poetry. It would have been a new book for him, having been published in 1874. Quaritch declares it ‘an invaluable collection, the result of thirty years’ labour on the part of the veteran author’. However, he has reservations, and once more we find him ready to air his own learning. ‘But he rashly meddles with comparative Philology’, he declares, with a figurative shake of the head, ‘and cites the Welsh word Aber, as akin to “Abri=out”, not within’. Tut-tut.

In his introduction, Quaritch puts himself forward as both a humble servant to the devoted book collector and as a bookseller without equal – a blend of the bullish and the self-effacing which manages to balance out. ‘No such Catalogue of valuable books and manuscripts...was ever before issued, and its unlikely that it ever can be done again’, he boasts. ‘Whether, further, any bookseller will be blessed with such uniform good health’, he continues, ‘such universality of range in all branches of Literature, and I may add, such a devotion to his trade, time alone will tell’. ‘To bring together this Collection of Books’, he goes on to assert, ‘to group them into Classes, to get them catalogued, place them systematically on my shelves, and to issue the Catalogue originally in sections...has been an immense labour, and has only been achieved by my intense desire to be a useful labourer in promoting the progress of civilisation’. A noble and high-minded ideal indeed. Quaritch concludes by outlining his ambitions for the continuation of his trade. ‘I may add’, he adds, ‘that I shall continue to deserve the patronage of my numerous Customers throughout the Globe by strict business rules and prompt attention to all their wants. A shilling pamphlet will be supplied as well as rare and fine books. It has been my endeavour to make my establishment a focus for learned men and book-collectors of every sort, in which they may find or readily obtain anything they require, either to make a Library or to follow up their literary and scientific pursuits. I trust, therefore, that my house will remain as it has been, useful to scholars and collectors from all countries. I will cheerfully devote the rest of my life to gratify their wishes and supply their wants’.

When his business had become established as one of the most reputable booksellers in the country, Quaritch set up premises in the highly prestigious Piccadilly area – number 16 to be precise. This was an area known in the nineteenth century for its booksellers and literary associations. Hatchards bookshop was established here in 1797 and Charles Dickens gave several readings in St James Hall, which was opened in 1858 and was just over the road, just two years before Quaritch moved to the area. By this time, his reputation for dominating the sale rooms whenever private collections were put up for auction earned him the epithet the Napoleon of Booksellers. In his 1900 obituary of Quaritch in The Atlantic magazine, Dean Sage, who had known him personally and had professional dealings with him, remarked that ‘He was truly the autocrat of the auction room, and nothing, apparently, stopped him when something came up that he wanted or fancied’. He also noted that "Mr Quaritch was a rare union of the merchant, the scholar, and the bibliopholist, with the added and indescribable literary quality which made him the delight of all who knew him. He was not a man of “blandishments ; ” on the contrary, his demeanor was rather forbidding to strangers. He was impatient of differences of opinion, especially on matters connected with books ; he was frank, sometimes unpleasantly so, in the expression of his views, and the openness of his egotism was amusing to some, and the reverse to others".

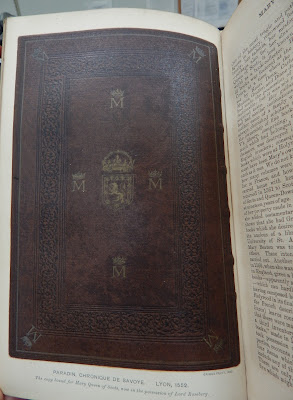

This experience afforded him an intimate knowledge of the private libraries of some of the most eminent collectors across the centuries. In the final decade of his life, the final decade of the nineteenth century indeed, he set to creating a grand work which would memorialise some of these collections, many of which he had helped to redistribute. He published a series of twelve pamphlets, the first printed in May 1892, which were designed to be bound into one handsome volume once complete. Quaritch’s death in December 1899 meant that it probably fell short of his ultimate ideal, but it is an impressive achievement nevertheless. We have a copy, and the quality of the collated book is immediately apparent. The paper is of a fine grade and there are numerous facsimiles of illustrations, illuminations, personal book-plates and covers from the books discussed, some of which are embossed, some on inserts which fold out to provide greater detail, and some which reproduce the different coloured inks used in the writing. It is fascinating to see some of Quaritch’s correspondence which is included throughout, although the handwriting which is replicated on the page is sometimes tricky to decipher.

The pamphlets went by the comprehensive if unwieldy title Contributions Towards A Dictionary of English Book-Collectors, As Also Of Some Foreign Collectors Whose Libraries Were Incorporated In English Collections Or Whose Books Are Chiefly Met With In England. The publisher is credited at the bottom of each pamphlet cover: London: Bernard Quaritch, 15 Picadilly. The roll-call of collectors is impressive, ranging from Archbishop Cranmer and Mary Stuart to the gothic novelist and tower-building wastrel William Beckford and contemporaries and personal acquaintances Edward Fitzgerald and Sir Richard Burton. Quaritch would have been present at any of the sales of these collections in the latter part of the nineteenth century. He certainly was at the Beckford sale, where his purchases accounted for over half of the sales totals. Quaritch laid out his stall on the back cover of the pamphlets. He declared ‘it is my intention to produce a dictionary of English book-collectors from the earliest recorded examples to the present time. Such a work can only be accomplished, even in a tentative and imperfect manner, by the collaboration of many hands. Although likely to be interesting as well as novel, it would be unremunerative; and I could not afford to pay for any literary assistance. The cost of paper and printing, and of the designs and engravings which may be required to illustrate the Dictionary – such as book-plates, armorial bearings, facsimiles of characteristic bindings, and the like – will be very heavy, and will, of course, be my own contribution to the achievement of the work’.

The entry on Edward Fitzgerald introduces us to one of Quaritch’s earliest publishing ventures which, after a disappointing start, proved to be one of his greatest. ‘The most fortunate circumstance of his literary career’, the entry tells us of Fitzgerald, ‘was his beginning about 1846-7 to read, with Professor EH Cowell (this should probably be EB Cowell – Edward Byles Cowell – and the date 1856-7) the remains of the Persian poet ‘Omar ibn al Khayyam, then to be found only in a MS. at the Bodleian. He was fascinated by the humour, pathos and scepticism of the Tetrastichs, written about eight hundred years ago; and he attempted to reproduce the spirit of the original in English by selecting sometimes whole quatrains, sometimes odd lines or passages, and weaving them altogether into a shape resembling that of the Persian, with a continuous strain of thought running through the recomposition, so as to give it the appearance of a homogeneous whole rather than of a collection of scattered and unconnected stanzas, which would be liker to the archetype’.

Quaritch published the first edition of what Fitzgerald titled The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam in 1859, when he was still at his Castle Street premises in Leicester Square, although Fitzgerald actually paid the printing costs for an initial print run of 250. He also published three further editions in 1868, 1872 and 1879. The book was not an immediate success, but was taken up by the Pre-Raphaelites (Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Algernon Swinburn were particular admirers) and became a cornerstone of the literature and art of fin-de-siecle decadence. It was central in establishing an exoticised view of the East, and of Arabic cultures in particular, something which has subsequently been examined and criticised in books such as Edward Said’s classic study Orientalism. Given the worldwide renown it had attained by the 1880s, Quaritch always enjoyed relating that he had put unsold copies of the original print run in the bargain boxes outside his shop for prices ranging from 5 shillings to a giveaway one penny. These can now sell for over £20,000.

We don’t have any of those original copies of the Rubaiyat, but we do have a number of other handsome editions. There is a 7 volume collection of Fitzgerald’s works with his Rubaiyat transtlations in volume 7, along with an introduction to the ‘astronomer-poet of Persia’. A luxurious 1911 edition with a gilded peacock on the cover renders the verses in illuminated calligraphy with sentimental Edwardian illustrations by F.Sangorski and G.Sutcliffe, who offer a distinctly Europeanised visualisation of the texts. And then there’s a 1930 reprint of a 1920 edition, a very jazz age version illustrated by Ronald Balfour (cousin to the British Prime Minister Arthur Balfour). His versions are like Aubrey Beardsley with a Louise Brooks bob. They take the license afforded by orientalism’s otherness to depict a highly eroticised imagining of the poems. The plates are largely black and white, with the occasional splash of bright colour, but occasionally they burst out in full Technicolor glory. When they do so, they have a strong stylistic resemblance to the children’s book illustrations of Edwardian artists such as Edmund Dulac and Kay Nielsen. Hopefully we might on a future occasion take a look at Dulac’s beautiful illustrations to Poe’s poetry which we have down in the ‘cage’ in the stacks.

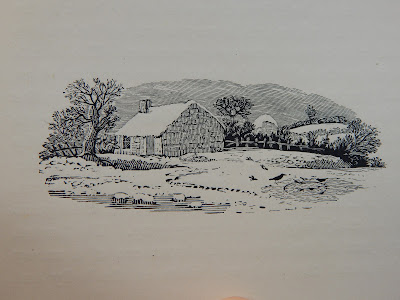

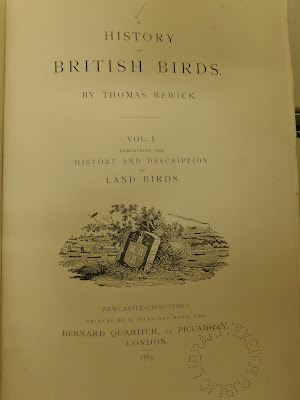

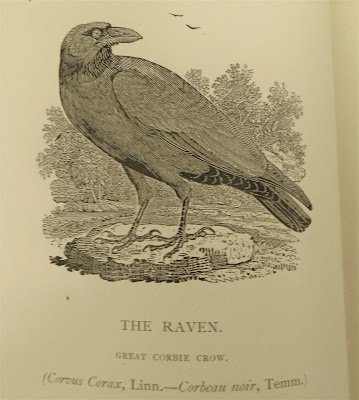

Quaritch’s publishing ventures also included a 5 volume ‘Memorial’ edition of the works of Thomas Bewick, which was issued in a limited run of 750 numbered copies in 1885. We have the whole set down in the cage area of the stack, and ours is numbered 44, with Bernard Quaritch’s signature appended in neat ink script. As we shall see, this is his restrained signature. He was capable of a flamboyent flourish of the pen when the mood took him. These books were printed in Newcastle, which is entirely appropriate since this is the city where Thomas Bewick lived for the greater part of his life. Bewick came from an ordinary background, the son of a tenant farmer and collier, and was apprenticed to an engraver named Ralph Beilby in Newcastle. It was an apprenticeship which developed into a business partnership as Bewick became skilled in the trade. The business was in metal engraving, but Bewick became interested in the art of wood engraving, which had become a neglected form at this time. A keen amateur naturalist, he began creating blocks for prints of animals with the idea of printing an illustrated book, working in the evenings after the official business of the day had been done. His General History of Quadrupeds was first published in 1790, and established his reputation on a national level. Two volumes of books on birds followed, the guide to Land Birds published in 1797 and Water Birds in 1804.

As fine as the animal and bird illustrations were, what gave the books their special character were the ‘tail pieces’ which filled up the spaces at the end of each section. These were tiny, exquisitely carved tableaux of rural life which were charming but which could also veer towards the macabre, the bawdily humorous or the mordantly philosophical. Here are hapless drunkards, useless scarecrows, daydreaming fishermen, rain-soaked travellers, supernatural encounters at woodland edges and memento mori in graveyards. Perhaps the darkest of these tailpieces features a man hanging from a tree on the edge of a river, his dog looking up at his body. I remember this image from my childhood, reproduced in a Readers Digest book of British Ghosts. It was clearly imprinted on my impressionable memory, and when I saw it again in the Quaritch edition, in the section on owls, I immediately recognised and thought ‘ah! That’s where that came from’. There is morbid humour in the use of the Lating phrase Sero Sed Serio. It means 'late but in earnest', and was (indeed probably still is) the motto of the Border Scottish Kerr clan. Bewick was no doubt aware of their history of divided loyalities. The invention, richness of character and ability to evoke the moods of weather and seasons make Bewick’s work the miniature equivalent of the Japanese woodblock prints of masters like Hiroshige and Hokusai. Quaritch’s quality editions show them off in the finely produced form they deserve. Perhaps he was drawn to Bewick because he saw echoes in his rise from humble beginnings through apprenticeship in his trade to national recognition of his own progress from his boyhood apprenticeship in the German book trade.

Whilst bookselling and purchasing was always the primary focus of Quaritch's business, his publishing seemed to become a major sideline, particularly in the 1890s. We have a number of books in the stack bearing the publisher's address: London: Bernard Quaritch, 15 Picadilly. They cover a surprisingly wide range of subjects. There's a lovely 6 volume set of William Morris' translations of the Icelandic sagas with gilded spines, gathered together under the title The Saga Library. A very handsome volume of Lady Charlotte Guest's translation of The Mabinogion was published in 1877, its red cover presumably denoting its provenance in the Red Book of Hergest. Elsewhere we find Freeman M. Donoghue's Descriptive and Classified Catalogue of Portraits of Queen Elizabeth (1894); Hewett Cottrell Watson's Topographical Botany (1883); John Mitchell Kemble's The Saxons in England (1876); Charles Elton's Origins of English History (1890); and not forgetting The Hon. Alicia Amherst's A History of Gardening in England (1896).

Some people say you can tell a lot about a person’s character from their handwriting. If so, then Quaritch’s is certainly hiding nothing. He has a flowing script full of baroque flourishes and swirling curves. Look at that ‘the’ at the start of the sentence ‘the last publication of the Kelmscott Press’. It certainly makes the most of this most ordinary of words, turning the upper bar of the T into a vaporous plume. But the signature is a magnificent thing. The Q is a spiral which circles out into an elegant downward swoop. It’s a letter which dances. The horizontal across the t expands across the final letters of the Quaritch name, executing a little squiggle at the end, as if giving a brief formal bow. We can imagine Quaritch writing this letter, dipping his nib in the inkwell before inscribing with elegant motions of the hand, the pen twirling and gliding across the page as if to the strains of a stately waltz. This is a script which clearly indicates a confident and expressive personality, certain of its authority but also with a playful and aesthetic sensibility.

Here’s what Quaritch writes in his letter: “Morris’ Caxton’s Golden Legends – there was no large paper edition published, all the printed copies were the same. The last publication of the Kelmscott Press is a little book entitled News from Nowhere, small quarto vellum price 2/2/- . Shall I send you a copy?

I remember seeing a notice that Sir Geo. Duckett was editing Visitation of Chapels General of the Order of Cluni. I will look into the matter and let you know subscription as soon as possible.” The fact that the library has a copy of the Kelmscott Press News From Nowhere suggests that Fisher may well have taken him up on his offer. As for George Duckett’s Visitations and Chapters-General of the Order of Cluni 1269-1529, which was published in 1893, we can but speculate.

Quaritch signs off ‘I remain Sir your obedient servant Bernard Quaritch’. This sentiment, which we have encountered previously, was seriously meant. Quaritch was nobody’s fool, and as the Atlantic obituary points out, he had no false modesty. In that piece, the author Dean Sage writes ‘he knew he was the greatest living bookseller, and mentioned the fact as something patent and irrefutable’. But Sage immediately goes on to add ‘he was also perfectly sincere in stating his willingness to devote his life to gratifying the wishes of scholars and collectors, and he did it’. He was no book snob, either, and was happy to devote as much effort to tracking down inexpensive volumes as to the grand historical tomes which might turn up at the sales of grand personages. His convivial side can be seen in his founding and participation in the Sette of Odd Volumes, a bibliophile club which met monthly to discuss bookish matters. Quaritch was thrice elected president of this club, the odd volumes of which were the members themselves. Books were his lifeblood and also his intellectual passion. Happily, the Quaritch bookshop continued to thrive after his death, and remained under family management until 1971. It is still there, a central part of the London bookselling trade, now located in Bedford Row, a short stroll away from the British Museum. Something of Quaritch’s spirit surely remains in the heady must of old books lining its shelves. And something of it can also be found in those monumental catalogues which stand out like great memorial blocks down in the stacks.

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

Comments

Post a Comment