Ghost Stories For Christmas, or Spectres from the Stacks

As the nights grow ever darker and we approach the shortest day (and thus the longest night) of the year, it is the season for ghost stories. For centuries, people have gathered around the hearth to tell pleasingly chilling tales of what might be lurking in the shadows beyond the flickering light. It was the Victorians who really made such tales of the supernatural a literary Christmas tradition. Mr Dickens played a major part in its establishment, of course, with the Christmas editions of the magazines he 'conducted', Household Words and All The Year Round, containing a number of ghost stories by various hands, including the great man himself. Many of these stories were written by female authors, who were able to make a living writing for the magazines and journals which proliferated in this period. We have collections of a number of these down in the stacks, so it seemed a good idea to a bit of supernatural sleuthing to see what spectres we might divine.

Dickens seemed like a good place to start, and I found the 1853 edition of Household Words with its second Round of Stories By The Christmas Fire. We don't have the first, from the 1852 Christmas edition, which is a shame as it includes Elizabeth Gaskell's The Old Nurse's Story, a fine slice of gothic. Here we have Eliza Lynn Linton's The Old Lady's Story, a tale which begins with a young girl's encounter with a supernatural spirit in an eerie old house. Linton was a regular contributor to Household Words and other Victorian journals such as Cornhill Magazine. As a writer, she achieved fincancial independence, and you might think she would be sympathetic to the nascent cause of women's rights and suffrage. However, she is best known today for her 1868 polemic The Girl of the Period, which rails against the idea of the 'liberated' woman, a theme which she continued to play over the following decades. That notwithstanding, The Old Nurse's Story creates a classic haunted house atmosphere in its opening scenes. You can hear a reading of the eerie opening half here.

The Christmas 1864 edition of All The Year Round, the successor to Household Words (and still 'conducted' by Charles Dickens) contained a lasting classic of the ghost story form amongst the tales told by the tennants of Mrs Lirriper's loding house. Mrs Lirriper, by the way, was one of Dickens' most popular characters at the time, although her fame has largely dwindled to nothing in the intervening years. Another Lodger Relates His Own Ghost Story is now more commonly known as The Phantom Coach and was written by Amelia B Edwards. It evokes a wintry northern landscape in fine fashion, and is a story in two parts. In the first our narrator Murray gets hopelessly lost on the moor as the snow grows heavier, and finds shelter in a remote cottage. He receives a cold and reluctant welcome, and falls into conversation with the aloof master of the house, who is part scientist part occult philosopher. He laments the tendency of modern, rationalist science to dismiss the supernatural. With the snow having ceased, Murray decides to leave this strange dwelling, which seems to inhabit a world decades past, and return to his own lodgings. He is told of a night mail coach which passes some miles away and sets out to catch it. However, it is a coach of a very different nature which he ends up boarding. You can hear what he encounters here.

Amelia B Edwards was a fascinating character, just the sort of person whom Eliza Lynn Linton would have derided in her proto Daily Mail articles. She was a keen Egyptologist and a fearless traveller. Her travel book A Thousand Miles Up the Nile was published in 1877 - we have a 1982 reprint down in the stacks. We also have an original 1873 copy of her book Untrodden Peaks and Unfrequented Valleys, whose very title evokes a sense of thrilling excitement and daring adventures. In terms of her creative endeavours, writing was something she settled on after a period as a composer and singer (she concentrated on operas) and as an artist. She was also a fine crack with a pistol and enjoyed riding. She was far from a sedentray, housebound writer rooted to her desk. Her close relationships were with women and she lived with her partner Ellen Drew Braysher until her death in 1892. There is something of a West Country connection too. They lived for several decades in Westbury-on-Trym near Bristol, and Edwards in buried in the churchyard of St Mary the Virgin in Henbury in Bristol. She lies beneath an Egyptian obelisk with a stone ankh at its base - the Egyptian symbol of life.

The Christmas 1866 edition of All the Year Round included another ghost story which was to become a much-anthologised classic. The tales here are all attached to the different branch lines which fan out from Mugby Junction, the station at which the character we first meet alights. Number 1 Branch Line introduces us to The Signalman, a story which is rooted in a superbly evoked sense of place. The setting, with its signal box planted near the dark mouth of a tunnel and at the bottom of a shadowy railway cutting is foreboding and unsettling in itself. It is terrain which invites the spectral, and spectres do indeed appear. Some may remember the fine adaptation made for the BBC Ghost Stories at Christmas strand in the 1970s, with Denholm Elliott as the haunted signalman.

Railways were a new source for the supernatural in the Victorian period, carving out a new landscape with its potential for eerie manifestations. Ten years after Dickens' haunted signalman, Mary E Penn wrote another signal box-based ghost story in the December 1876 issue of The Argosy magazine, edited by Mrs Henry Wood (a writer who also contributed substantially to its contents). At Ravenholme Junction features a tragic ghost, a variant of Dickens' troubled signalman, and also conjures up the haunting sounds of the railway, with the wind humming through the telegraph wires and a phantom train shrieking its whistle through the rain-lashed night. There is an excellent steel-engraving illustration to the story, with the signalman's lantern shining right through the phantom figure. Little seems to be known about Mary E Penn, other than that she wrote a handful of excellent ghost stories and disappeared from literary view in 1897. You can hear a reading of the entire story here.

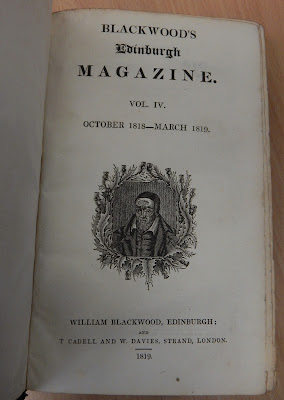

Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine was known for its gothic fiction, so much so that Edgar Allan Poe was able to write a satirical guide entitled 'How to Write a Blackwood Article' (he should know). The January 1882 issue included Mary Oliphant's tale The Open Door. This is another excellent ghost story which centres around a haunting in the ruins of an old house which is in the grounds of a manor on the outskirts of Edinburgh. It is newly occupied by our narrator, Colonel Mortimer, along with his family. The haunting is somehow linked to the illness of his son, Roland, a sensitive soul who has made an empathetic connection to the spectral figure which he has heard by the ruined doorway of the old house, now an isolated arch open to the elements. The Colonel must overcome his scepticism and 'lay' the ghost in order that his son may regain his health. In the shadowy night, the gnarled form of what appears to be a juniper bush hunches darkly by the rubble strewn doorway. But why does it appear to move from one side to the other? You can hear a reading of part of the story here.

Margaret Oliphant was a Scottish author who made frequent contributions to Blackwoods Edinburgh Magazine, and knew its founder, William Blackwood. Amongst her voluminous fiction and journalism, there are a number of ghost stories, including the longer length A Beleaguered City from 1879, subtitled 'A Story of the Seen and the Unseen'. We have an 1881 copy down in the stacks if you wanted to explore these uncanny realms.

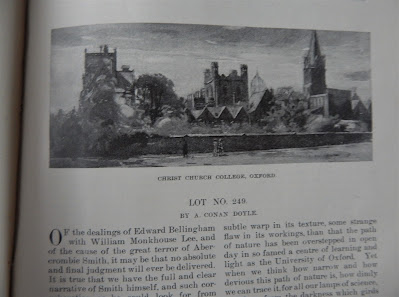

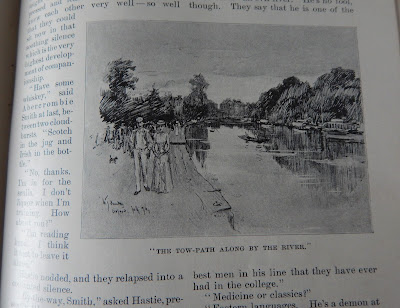

I've mentioned the BBC Ghost Stories for Christmas adaptations, a tradition established in the 1970s which produced some wonderfully chilling moments. It was revived recently with Mark Gattiss at the writing helm, turning mainly to M.R.James for source material. This year, however, he has chosen to adapt an Arthur Conan Doyle tale of the supernatural, Lot 249. It's an Oxford University set tale, and involves an unpopular and self-absorbed student who is an obsessive Egyptologist. His rooms are filled with Egyptian relics, amongst which is the newly acquired Lot 249. When you learn that this is a sarcophagus containing a mummy, you can probably tell where things are heading. Although possibly not the underlying psychological thrust of the story. We have the copy of Harper's Monthly Magazine from 1892 in which the story was first published. The final illustration is particularly enjoyable, in a grisly, nightmarish way.

Back to Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, way back in fact to 1818. One of the tales which helped gain the magazine a reputation for gothic gruesomeness was Daniel Keyte Sandford's A Night in the Catacombs. This is a short story about a highly wrought narrator who wanders off on a tour of the Paris catacombs, those underground passages and chambers filled with the stacked up bones of the dead. In the bony darkness, his imagination works overtime, and the writing feverishly evokes the horror of his hallucinatory experience. Sandford was an Edinburgh born boy, the son of the Right Reverend Daniel Sandford, Bishop of Edinburgh. He was a professor of Greek and, very briefly, a MP. But he clearly had a taste for horror as well.

Our final story comes from the pages of Harper's Monthly Magazine from 1893. At the Hermitage by E.Levi Brown is not strictly speaking a ghost story, more a tale of dark magic and malevolent spirits. It's a powerful story, and one which evokes not the chill climes of northern England, but the heated swamps of Southern gothic territory. E.Levi Brown was in fact Mrs E Levi Brown, wife of a minister in the American South. She was an African American woman and the characters here are also African Americans living in the South of the time. This appears to have been her only published story, and its importance lies not only in its quality but in its portrayal of African American lives in a voice that its author new from first hand experience.

So, we have somehow arrived in the American South from Dickensian tales told around the fireside and phantom coaches riding across snowbound moors. All of which goes to show the variety of material to be found in the nineteenth century journals, just waiting to be unearthed from the shadowy spaces of the stacks (which may or may not be haunted).

Comments

Post a Comment